3.6.1. Structure of the gut

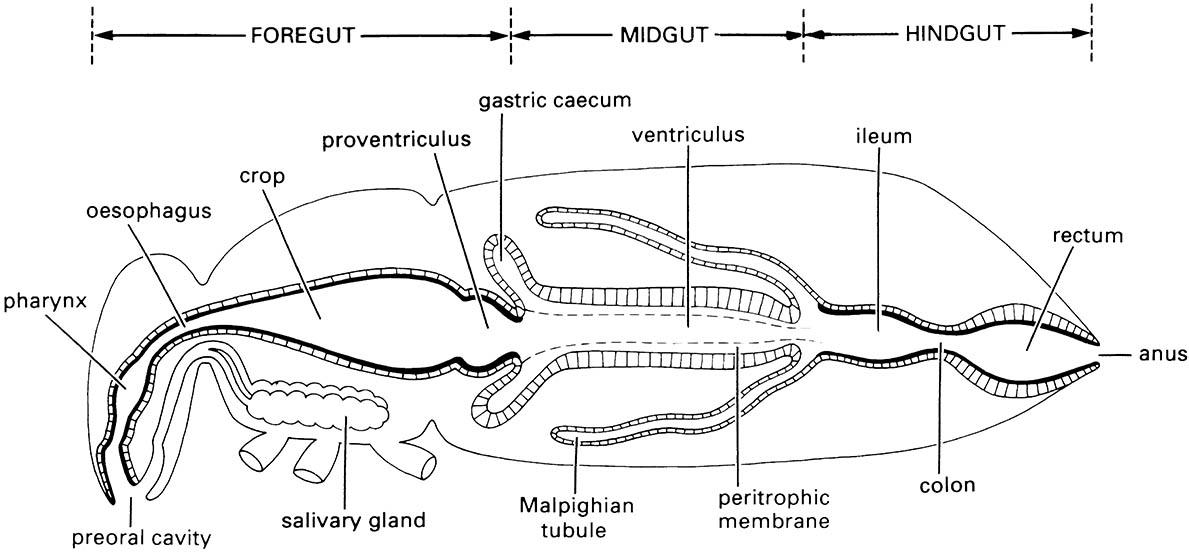

There are three main regions to the insect gut (or alimentary canal), with sphincters (valves) controlling food—fluid movement between regions (Fig. 3.13). The foregut (stomodeum) is concerned with ingestion, storage, grinding, and transport of food to the next region, the midgut (mesenteron). Here digestive enzymes are produced and secreted and absorption of the products of digestion occurs. The material remaining in the gut lumen together with urine from the Malpighian tubules then enters the hindgut (proctodeum), where absorption of water, salts, and other valuable molecules occurs prior to elimination of the feces through the anus. The gut epithelium is one cell layer thick throughout the length of the canal and rests on a basement membrane surrounded by a variably developed muscle layer. Both the foregut and hindgut have a cuticular lining, whereas the midgut does not.

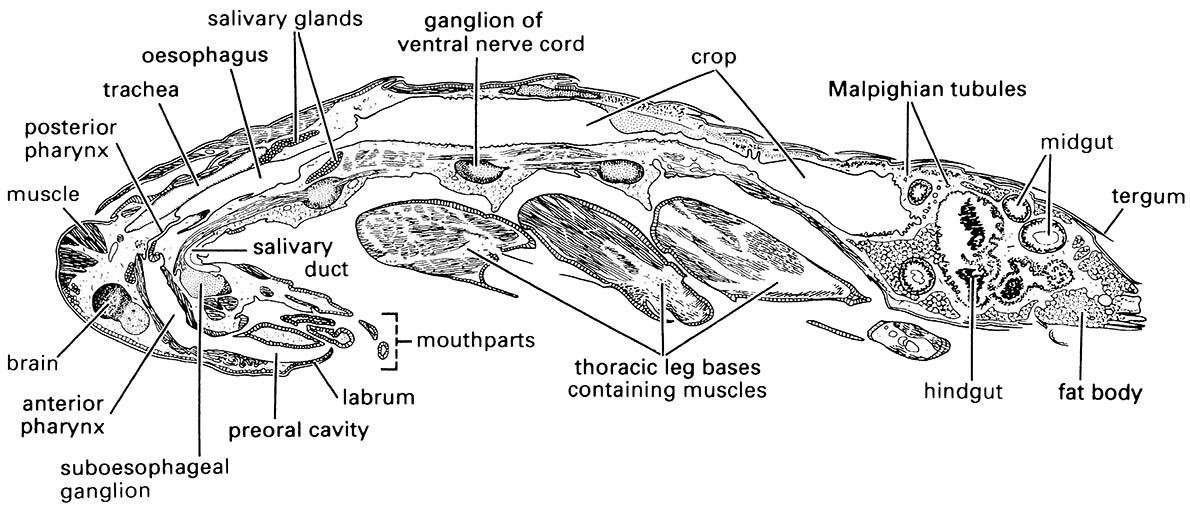

Each region of the gut displays several local specializations, which are variously developed in different insects, depending on diet. Typically the foregut is subdivided into a pharynx, an oesophagus (esophagus), and a crop (food storage area), and in insects that ingest solid food there is often a grinding organ, the proventriculus (or gizzard). The proventriculus is especially well developed in orthopteroid insects, such as cockroaches, crickets, and termites, in which the epithelium is folded longitudinally to form ridges on which the cuticle is armed with spines or teeth. At the anterior end of the foregut the mouth opens into a preoral cavity bounded by the bases of the mouthparts and often divided into an upper area, or cibarium, and a lower part, or salivarium (Fig. 3.14a). The paired labial or salivary glands vary in size and arrangement from simple elongated tubes to complex branched or lobed structures.

Complicated glands occur in many Hemiptera that produce two types of saliva (see section 3.6.2). In Lepidoptera, the labial glands produce silk, whereas mandibular glands secrete the saliva. Several types of secretory cell may occur in the salivary glands of one insect. The secretions from these cells are transported along cuticular ducts and emptied into the ventral part of the preoral cavity. In insects that store meals in their foregut, the crop may take up the greater portion of the food and often is capable of extreme distension, with a posterior sphincter controlling food retention. The crop may be an enlargement of part of the tubular gut (Fig. 3.7) or a lateral diverticulum.

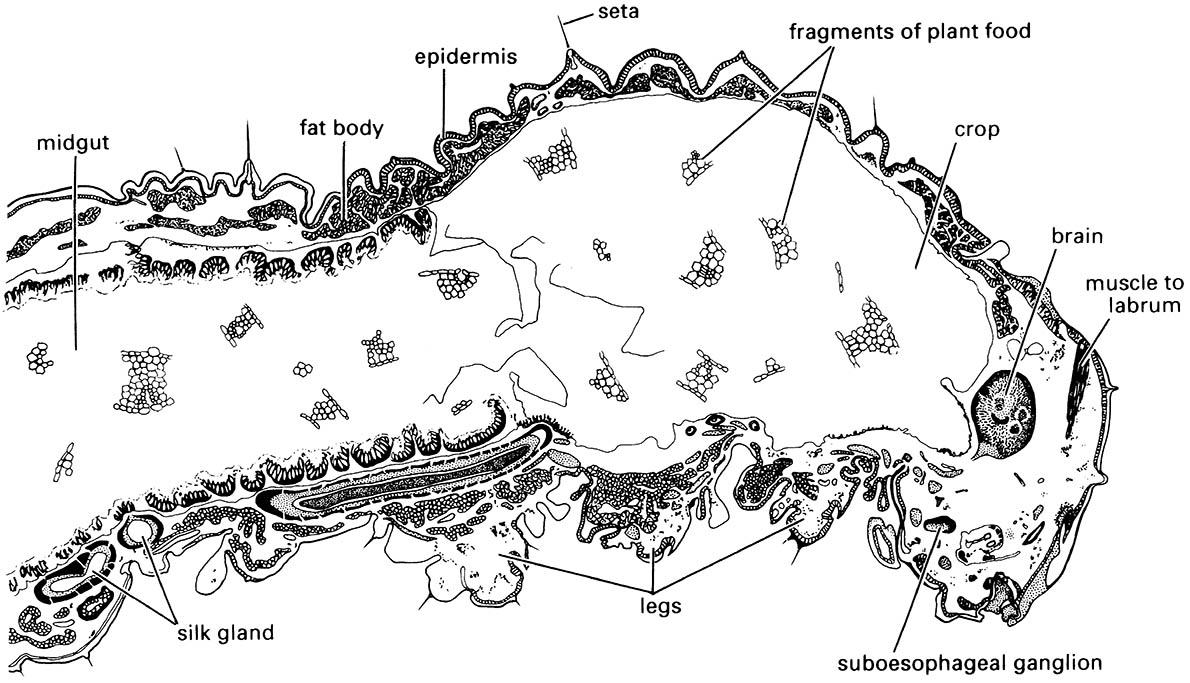

The generalized midgut has two main areas — the tubular ventriculus and blind-ending lateral diverticula called caeca (ceca). Most cells of the midgut are structurally similar, being columnar with microvilli (finger-like protrusions) covering the inner surface. The distinction between the almost indiscernible foregut epithelium and the thickened epithelium of the midgut usually is visible in histological sections (Fig. 3.15). The midgut epithelium mostly is separated from the food by a thin sheath called the peritrophic membrane, consisting of a network of chitin fibrils in a protein—glycoprotein matrix. These proteins, called peritrophins, may have evolved from gastrointestinal mucus proteins by acquiring the ability to bind chitin. The peritrophic membrane either is delaminated from the whole midgut or produced by cells in the anterior region of the midgut. Exceptionally Hemiptera and Thysanoptera lack a peritrophic membrane, as do just the adults of several other orders.

Typically, the beginning of the hindgut is defined by the entry point of the Malpighian tubules, often into a distinct pylorus forming a muscular pyloric sphincter, followed by the ileum, colon, and rectum. The main functions of the hindgut are the absorption of water, salts, and other useful substances from the feces and urine; a detailed discussion of structure and function is presented in section 3.7.1.

The cuticular lining of the foregut and hindgut are indicated by thicker black lines. (After Dow 1986)

Musculature of the mouthparts and the (a) pharyngeal or (b) cibarial pump are indicated but not fully labeled. Contraction of the respective dilator muscles causes dilation of the pharynx or cibarium and fluid is drawn into the pump chamber. Relaxation of these muscles results in elastic return of the pharynx or cibarial walls and expels food upwards into the oesophagus. (After Snodgrass 1935)

Note the thickened epidermal layer lining the midgut.