4.4.5. Light production

The most spectacular visual displays of insects involve light production, or bioluminescence. Some insects co-opt symbiotic luminescent bacteria or fungi, but self-luminescence is found in a few Collembola, one hemipteran (the fulgorid lantern bug), a few dipteran fungus gnats, and a diverse group amongst several families of coleopterans. The beetles are members of the Phengodidae, Drilidae, some lesser known families, and notably the Lampyridae, and are commonly given colloquial names including fireflies, glow worms, and lightning bugs. Any or all stages and sexes in the life history may glow, using one to many luminescent organs, which may be located nearly anywhere on the body. Light emitted may be white, yellow, red, or green.

The light-emitting mechanism studied in the lampyrid firefly Photinus pyralis may be typical of luminescent Coleoptera. The enzyme luciferase oxidizes a substrate, luciferin, in the presence of an energy source of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) and oxygen, to produce oxyluciferin, carbon dioxide, and light. Variation in ATP release controls the rate of flashing, and differences in pH may allow variation in the frequency (color) of light emitted.

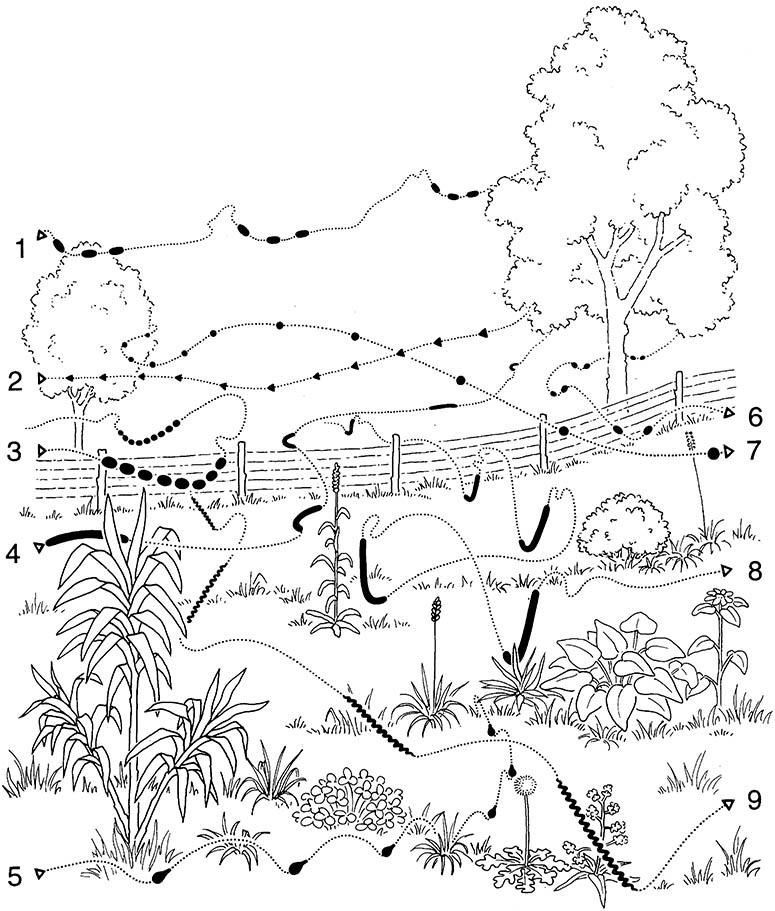

The principal role of light emission was argued to be in courtship signaling. This involves species-specific variation in the duration, number, and rate of flashes in a pattern, and the frequency of repetition of the pattern (Fig. 4.11). Generally, a mobile male advertises his presence by instigating the signaling with one or more flashes and a sedentary female indicates her location with a flash in response. As with all communication systems, there is scope for abuse, for example that involving luring of prey by a carnivorous female lampyrid of Photurus (section 13.1.2). Recent phylogenetic studies have suggested a rather different inter- pretation of beetle bioluminescence, with it originating only in larvae of a broadly defined lampyrid clade, where it serves as a warning of distastefulness (section 14.4). From this origin in larvae, luminescence appears to have been retained into the adults, serving dual warning and sexual functions. The phylogeny suggests that luminescence then was lost in lampyrid relatives and regained subsequently in the Phengodidae, in which it is present in larvae and adults and fulfills a warning function. In this family it is possible that light is used also in illuminating a landing or courtship site, and perhaps red light serves for nocturnal prey detection.

Bioluminescence is involved in both luring prey and mate-finding in Australian and New Zealand cave-dwelling Arachnocampa fungus gnats (Diptera: Mycetophilidae). Their luminescent displays in the dark zone of caves have become tourist attractions in some places. All developmental stages of these flies use a reflector to concentrate light that they produce from modified Malpighian tubules. In the dark zone of a cave, the larval light lures prey, particularly small flies, onto a sticky thread suspended by the larva from the cave ceiling. The flying adult male locates the luminescent female while she is still in the pharate state and waits for the opportunity to mate upon her emergence.

(After Lloyd 1966)