5.2. Courtship

Although the long-range attraction mechanisms dis- cussed above reduce the number of species present at a prospective mating site, generally there remains an excess of potential partners. Further discrimination among species and conspecific individuals usually takes place. Courtship is the close-range, intersexual behavior that induces sexual receptivity prior to (and often during) mating and acts as a mechanism for species recognition. During courtship, one or both sexes seek to facilitate insemination and fertilization by influencing the other’s behavior.

Courtship may include visual displays, predominantly by males, including movements of adorned parts of the body, such as antennae, eyestalks, and “picture” wings, and ritualized movements (“dancing”). Tactile stimulation such as rubbing and stroking often occurs later in courtship, often immediately prior to mating, and may continue during copulation. Antennae, palps, head horns, external genitalia, and legs are used in tactile stimulation.

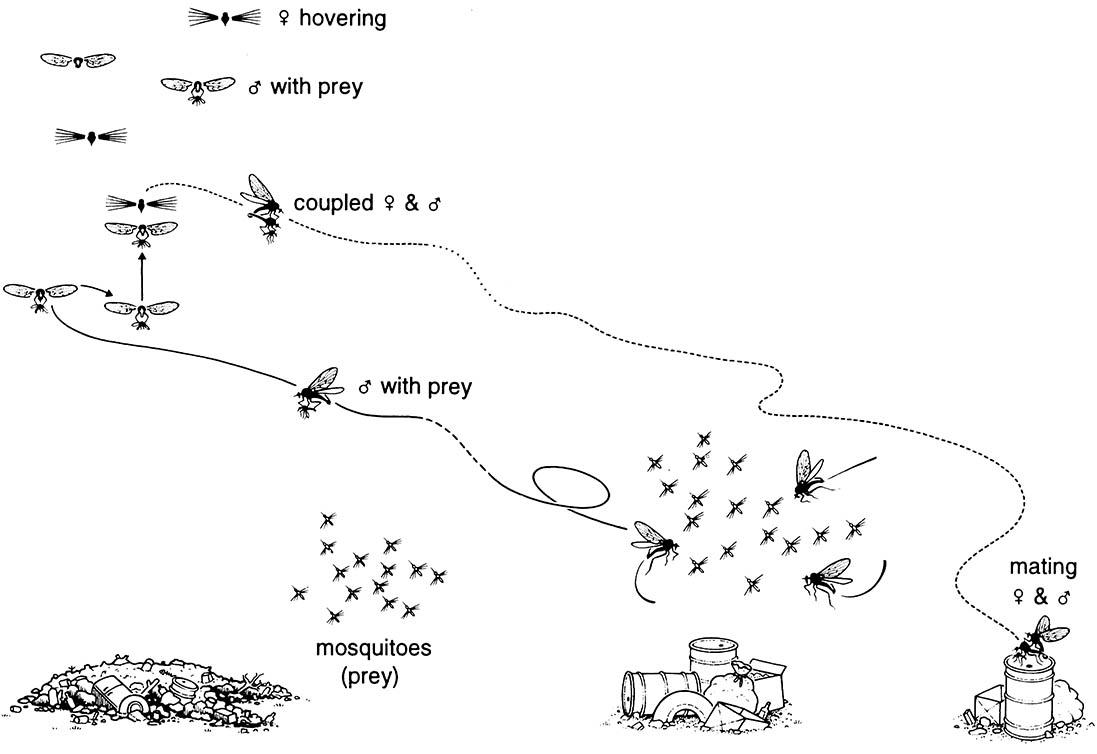

Insects such as crickets, which use long-range calling, may have different calls for use in close-range courtship. Others, such as fruit flies (Drosophila), have no long-distance call and sing (by wing vibration) only in close-up courtship. In some predatory insects, including empidid flies and mecopterans, the male courts a prospective mate by offering a prey item as a nuptial gift (Fig. 5.1; Box 5.1).

If the sequence of display proceeds correctly, court- ship grades into mating. Sometimes the sequence need not be completed before copulation commences. On other occasions courtship must be prolonged and repeated. It may be unsuccessful if one sex fails to respond or makes inappropriate responses. Generally, members of different species differ in some elements of their courtships and interspecies matings do not occur. The great specificity and complexity of insect courtship behaviors can be interpreted in terms of mate location, synchronization, and species recognition, and viewed as having evolved as a premating isolating mechanism. Important as this view is, there is equally compelling evidence that court- ship is an extension of a wider phenomenon of competitive communication and involves sexual selection.

Swarms of both the empidids and the mosquitoes form near conspicuous landmarks, including refuse heaps or oil drums that are common in parts of the tundra. Within the mating swarm (upper left), a male empidid rises towards a female hovering above, they pair, and the prey is transferred to the female; the mating pair alights (lower far right) and the female feeds as they copulate. Females app ear to obtain food only via males and, as individual prey items are small, must mate repeatedly to obtain sufficient nutrients to develop a batch of eggs. (After Downes 1970)