9.5.3. Fungus cultivation by termites

The terrestrial microfauna of tropical savannas (grass- lands and open woodlands) and some forests of the Afrotropical and Oriental (Indo-Malayan) zoogeographic regions can be dominated by a single subfamily of Termitidae, the Macrotermitinae. These termites may form conspicuous above-ground mounds up to 9 m high, but more often their nests consist of huge under- ground structures. Abundance, density, and produc- tion of macrotermitines may be very high and, with estimates of a live biomass of 10 g m-2, termites consume over 25% of all terrestrial litter (wood, grass, and leaf) produced annually in some west African savannas.

The litter-derived food resources are ingested, but not digested by the termites: the food is passed rapidly through the gut and, upon defecation, the undigested feces are added to comb-like structures within the nest. The combs may be located within many small subterranean chambers or one large central hive or brood chamber. Upon these combs of feces, a Termitomyces fungus develops. The fungi are restricted to Macro-termitinae nests, or occur within the bodies of termites. The combs are constantly replenished and older parts eaten, on a cycle of 5–8 weeks. Fungus action on the termite fecal substrate raises the nitrogen content of the substrate from about 0.3% until in the asexual stages of Termitomyces it may reach 8%. These asexual spores (mycotêtes) are eaten by the termites, as well as the nutrient-enriched older comb. Although some species of Termitomyces have no sexual stage, others develop above-ground basidiocarps (fruiting bodies, or “mush- rooms”) at a time that coincides with colony-founding forays of termites from the nest. A new termite colony is inoculated with the fungus by means of asexual or sexual spores transferred in the gut of the founder termite(s).

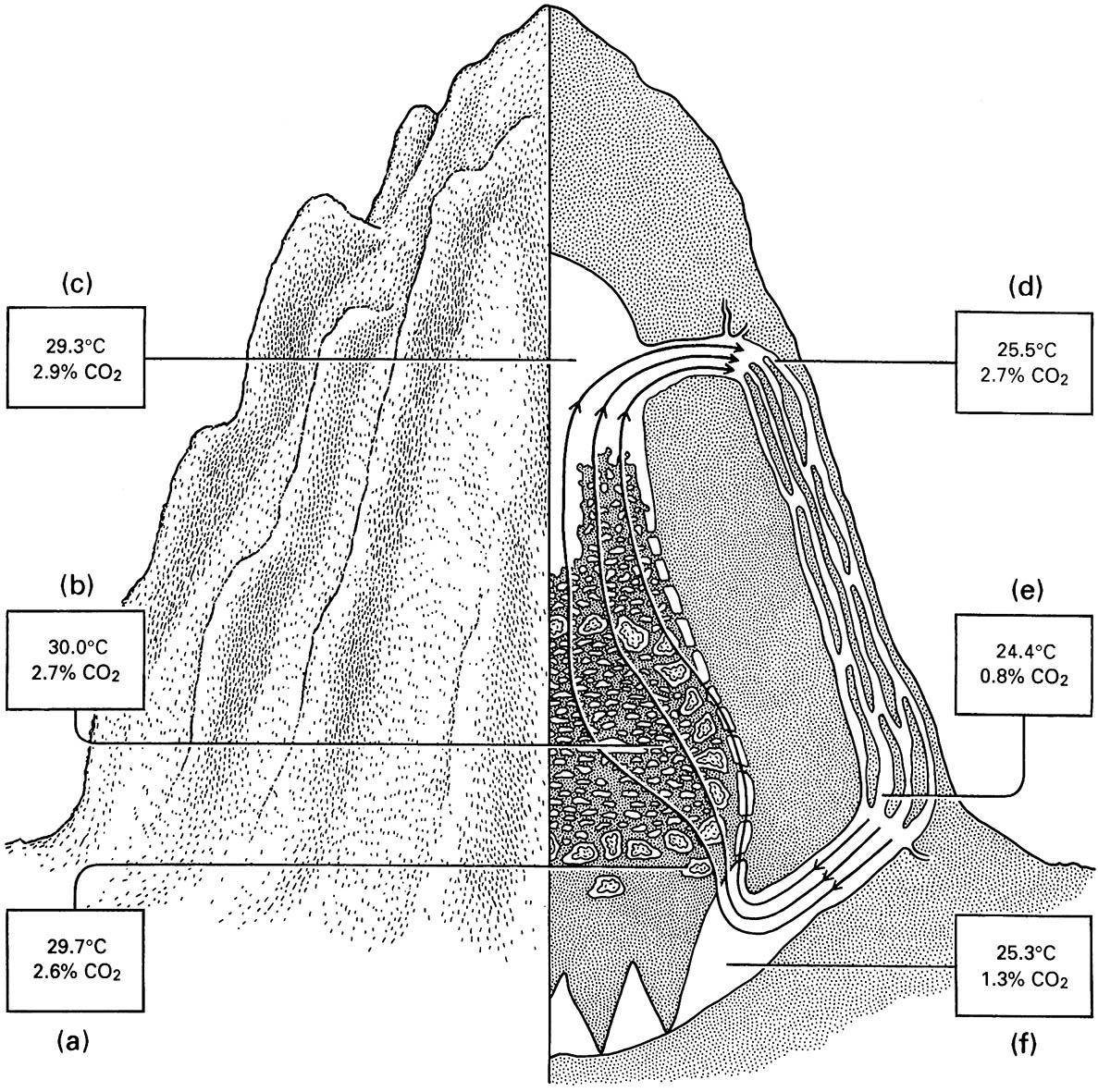

Termitomyces lives as a monoculture on termite-attended combs, but if the termites are removed experimentally or a termite colony dies out, or if the comb is extracted from the nest, many other fungi invade the comb and Termitomyces dies. Termite saliva has some antibiotic properties but there is little evidence for these termites being able to reduce local competition from other fungi. It seems that Termitomyces is favored in the fungal comb by the remarkably constant microclimate at the comb, with a temperature of 30°C and scarcely varying humidity together with an acid pH of 4.1–4.6. The heat generated by fungal metabolism is regulated appropriately via a complex circulation of air through the passageways of the nest, as illustrated for the above-ground nest of the African Macrotermes natalensis in Fig. 12.10.

The origin of the mutualistic relationship between termite and fungus seems not to derive from joint attack on plant defenses, in contrast to the ant—fungus interaction seen in section 9.5.2. Termites are associated closely with fungi, and fungus-infested rotting wood is likely to have been a primitive food preference. Termites can digest complex substances such as pectins and chitins, and there is good evidence that they have endogenous cellulases, which break down dietary cellulose. However, the Macrotermitinae have shifted some of their digestion to Termitomyces outside of the gut. The fungus facilitates conversion of plant compounds to more nutritious products and probably allows a wider range of cellulose-containing foods to be consumed by the termites. Thus, the macrotermitines successfully utilize the abundant resource of dead vegetation.

Measurements of temperature and carbon dioxide are shown in the boxes for the following locations: (a) the fungus combs; (b) the brood chambers; (c) the attic; (d) the upper part of a ridge channel; (e) the lower pa rt of a ridge channel; and (f ) the cellar. (After Lüscher 1961)