9.2. Insects and dead trees or decaying wood

The death of trees may involve insects that play a role in the transmission of pathogenic fungi amongst trees. Thus, wood wasps of the genera Sirex and Urocercus (Hymenoptera: Siricidae) carry Amylostereum fungal spores in invaginated intersegmental sacs connected to the ovipositor. During oviposition, spores and mucus are injected into the sapwood of trees, notably Pinus species, causing mycelial infection. The infestation causes locally drier conditions around the xylem, which is optimal for development of larval Sirex. The fungal disease in Australia and New Zealand can cause death of fire-damaged trees or those stressed by drought conditions. The role of bark beetles (Scolytus spp., Coleoptera: Curculionidae: Scolytinae) in the spread of Dutch elm disease is discussed in section 4.3.3. Other insect-borne fungal diseases transmitted to live trees may result in tree mortality, and continued decay of these and those that die of natural causes often involves further interactions between insects and fungi.

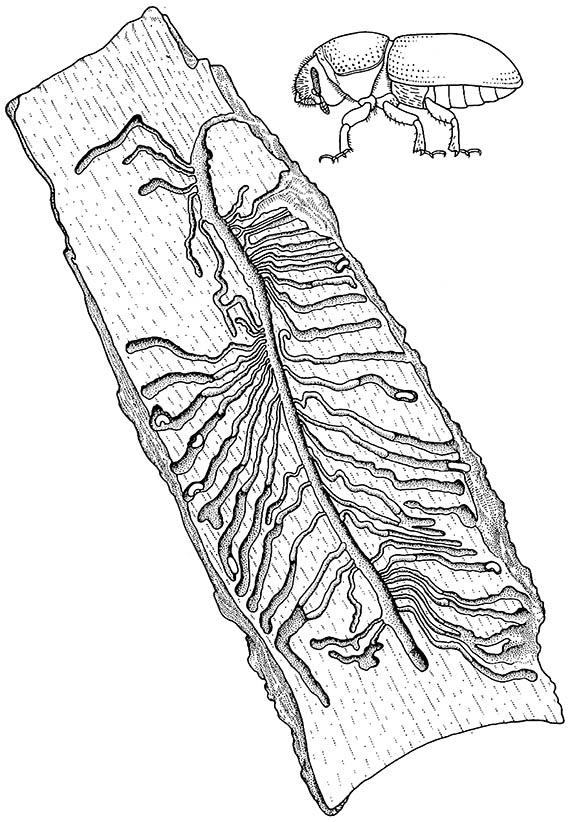

The ambrosia beetles (Curculionidae: Platypodinae and some Scolytinae) are involved in a notable association with ambrosia fungus and dead wood, which has been popularly termed “the evolution of agriculture” in beetles. Adult beetles excavate tunnels (often called galleries), predominantly in dead wood (Fig. 9.3), although some attack live wood. Beetles mine in the phloem, wood, twigs, or woody fruits, which they infect with wood-inhabiting ectosymbiotic “ambrosia” fungi that they transfer in special cuticular pockets called mycangia, which store the fungi during the insects’ aestivation or dispersal. The fungi, which come from a wide taxonomic range, curtail plant defenses and break down wood making it more nutritious for the beetles. Both larvae and adults feed on the conditioned wood and directly on the extremely nutritious fungi. The association between ambrosia fungus and beetles appears to be very ancient, perhaps originating as long ago as 60 million years with gymnosperm host trees, but with subsequent increased diversity associated with multiple transfers to angiosperms.

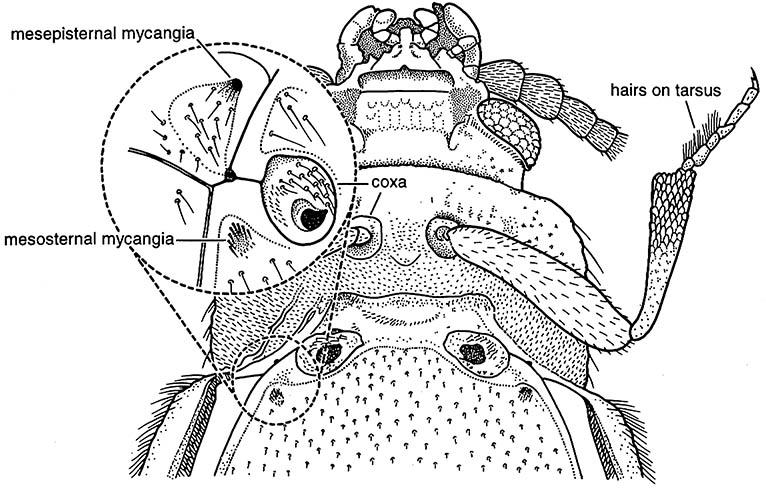

Some mycophagous insects, including beetles of the families Lathridiidae and Cryptophagidae, are strongly attracted to recently burned forest to which they carry fungi in mycangia. The cryptophagid beetle Henoticus serratus, which is an early colonizer of burned forest in some areas of Europe, has deep depressions on the underside of its pterothorax (Fig. 9.4), from which glandular secretions and material of the ascomycete fungus Trichoderma have been isolated. The beetle probably uses its legs to fill its mycangia with fungal material, which it transports to newly burnt habitats as an inoculum. Ascomycete fungi are important food sources for many pyrophilous insects, i.e. species strongly attracted to burning or newly burned areas or which occur mainly in burned forest for a few years after the fire. Some predatory and wood-feeding insects are also pyrophilous. A number of pyrophilous heteropterans (Aradidae), flies (Empididae and Platypezidae), and beetles (Carabidae and Buprestidae) have been shown to be attracted to the heat or smoke of fires, and often from a great distance. Species of jewel beetle (Buprestidae: Melanophila and Merimna) locate burnt wood by sensing the infrared radiation typically produced by forest fires (section 4.2.1).

Fallen, rotten timber provides a valuable resource for a wide variety of detritivorous insects if they can overcome the problems of living on a substrate rich in cellulose and deficient in vitamins and sterols. Termites are able to live entirely on this diet, either through the possession of cellulase enzymes in their digestive systems and the use of gut symbionts (section 3.6.5) or with the assistance of fungi (section 9.5.3). Cockroaches and termites have been shown to produce endogenous cellulase that allows digestion of cellulose from the diet of rotting wood. Other xylophagous (wood-eating) strategies of insects include very long life cycles with slow development and probably the use of xylophagous microorganisms and fungi as food.

(After Deyrup 1981)

(After drawing by Göran Sahlén in Wikars 1997)