9.3. Insects and dung

The excreta or dung produced by vertebrates may be a rich source of nutrients. In the grasslands and range-lands of North America and Africa, large ungulates produce substantial volumes of fibrous and nitrogen-rich dung that contains many bacteria and protists. Insect coprophages (dung-feeding organisms) utilize this resource in a number of ways. Certain higher flies — such as the Scathophagidae, Muscidae (notably the worldwide house fly, Musca domestica, the Australian M. vetustissima, and the widespread tropical buffalo fly, Haematobia irritans), Faniidae, and Calliphoridae — oviposit or larviposit into freshly laid dung. Development can be completed before the medium becomes too desiccated. Within the dung medium, predatory fly larvae (notably other species of Muscidae) can seriously reduce survival of coprophages. However, in the absence of predators or disturbance of the dung, nuisance-level populations of flies can be generated from larvae developing in dung in pastures.

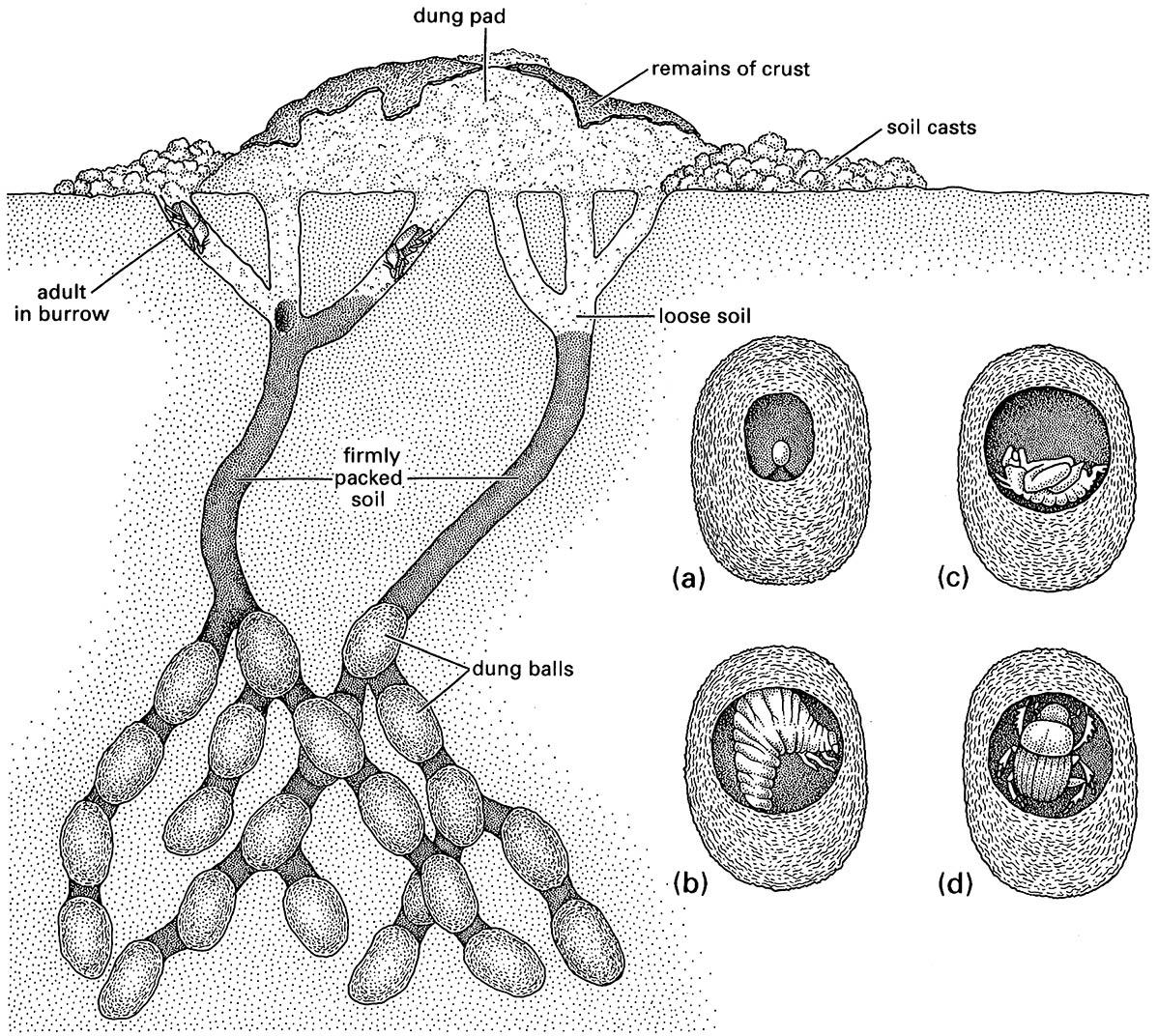

The insects primarily responsible for disturbing dung, and thereby limiting fly breeding in the medium, are dung beetles, belonging to the family Scarabaeidae. Not all larvae of scarabs use dung: some ingest general soil organic matter, whereas some others are herbivorous on plant roots. However, many are coprophages. In Africa, where many large herbivores produce large volumes of dung, several thousand species of scarabs show a wide variety of coprophagous behaviors. Many can detect dung as it is deposited by a herbivore, and from the time that it falls to the ground invasion is very rapid. Many individuals arrive, perhaps up to many thousands for a single fresh elephant dropping. Most dung beetles excavate networks of tunnels immediately beneath or beside the pad (also called a pat), and pull down pellets of dung (Fig. 9.5). Other beetles excise a chunk of dung and move it some distance to a dug-out chamber, also often within a network of tunnels. This movement from pad to nest chamber may occur either by head-butting an unformed lump, or by rolling molded spherical balls over the ground to the burial site. The female lays eggs into the buried pellets, and the larvae develop within the fecal food ball, eating fine and coarse particles. The adult scarabs also may feed on dung, but only on the fluids and finest particulate matter. Some scarabs are generalists and utilize virtually any dung encountered, whereas others specialize according to texture, wetness, pad size, fiber content, geographical area, and climate; a range of scarab activities ensures that all dung is buried within a few days at most.

In tropical rainforests, an unusual guild of dung beetles has been recorded foraging in the tree canopy on every subcontinent. These specialist coprophages have been studied best in Sabah, Borneo, where a few species of Onthophagus collect the feces of primates (such as gibbons, macaques, and langur monkeys) from the foliage, form it into balls and push the balls over the edge of leaves. If the balls catch on the foliage below, then the dung-rolling activity continues until the ground is reached.

In Australia, a continent in which native ungulates are absent, native dung beetles cannot exploit the volume and texture of dung produced by introduced domestic cattle, horses, and sheep. As a result, dung once lay around in pastures for prolonged periods, reducing the quality of pasture and allowing the development of prodigious numbers of nuisance flies. A program to introduce alien dung beetles from Africa and Mediterranean Europe has been successful in accelerating dung burial in many regions.

The inset shows an individual dung ball within which beetle development takes place: (a) egg; (b) larva, which feeds on the dung; (c) pupa; and (d) adult just prior to emergence. (After Waterhouse 1974)