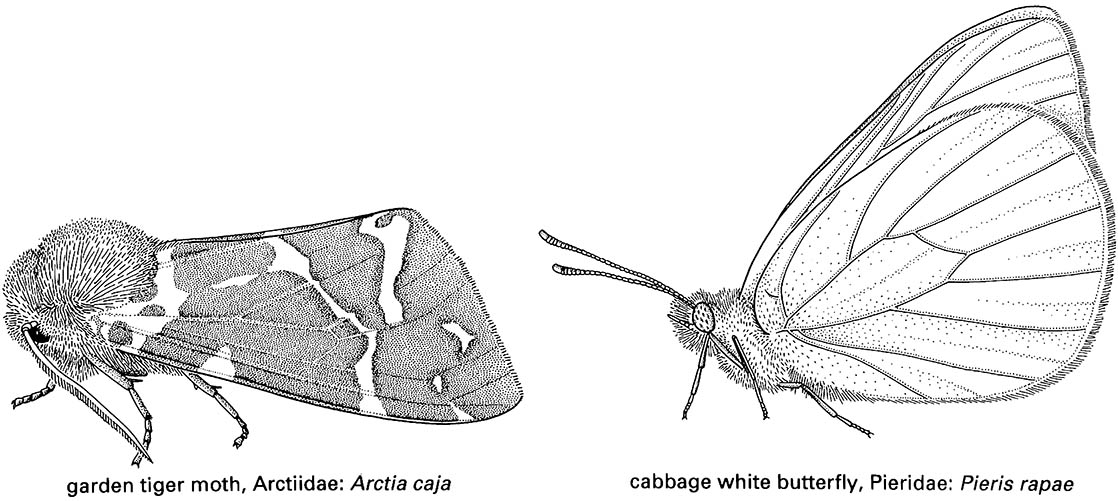

Box 11.11. Lepidoptera (butterflies and moths)

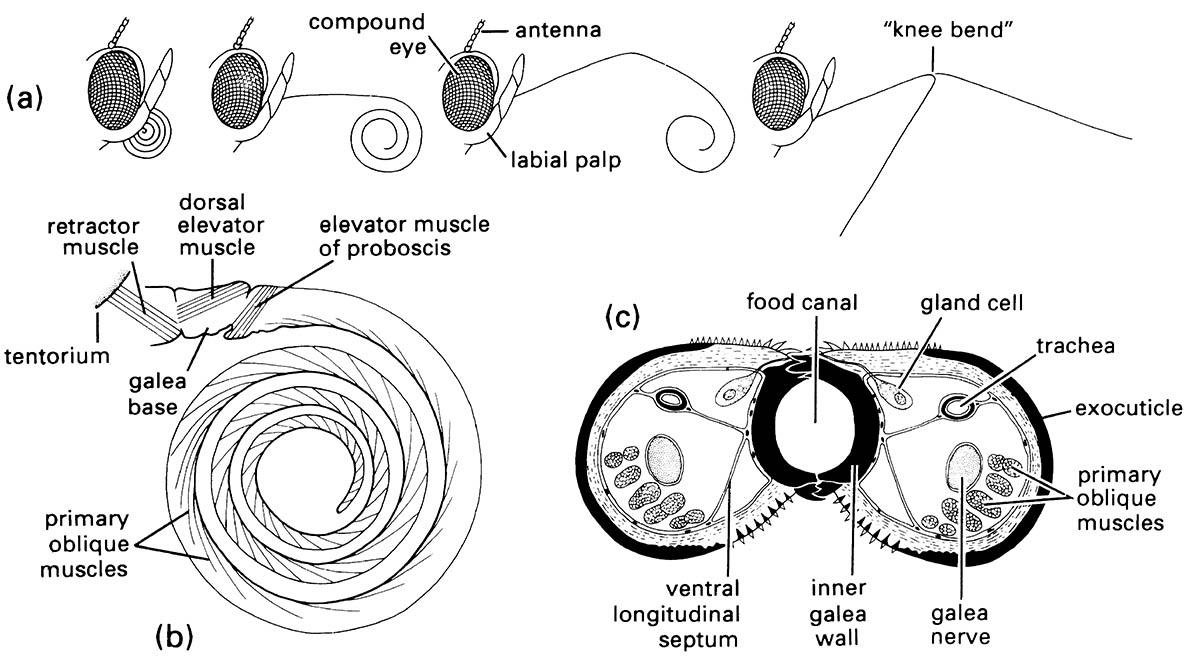

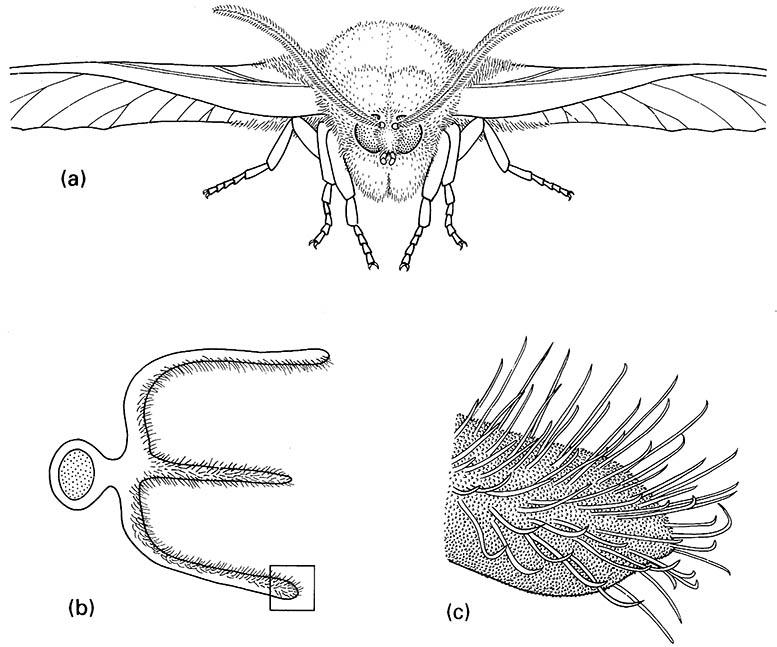

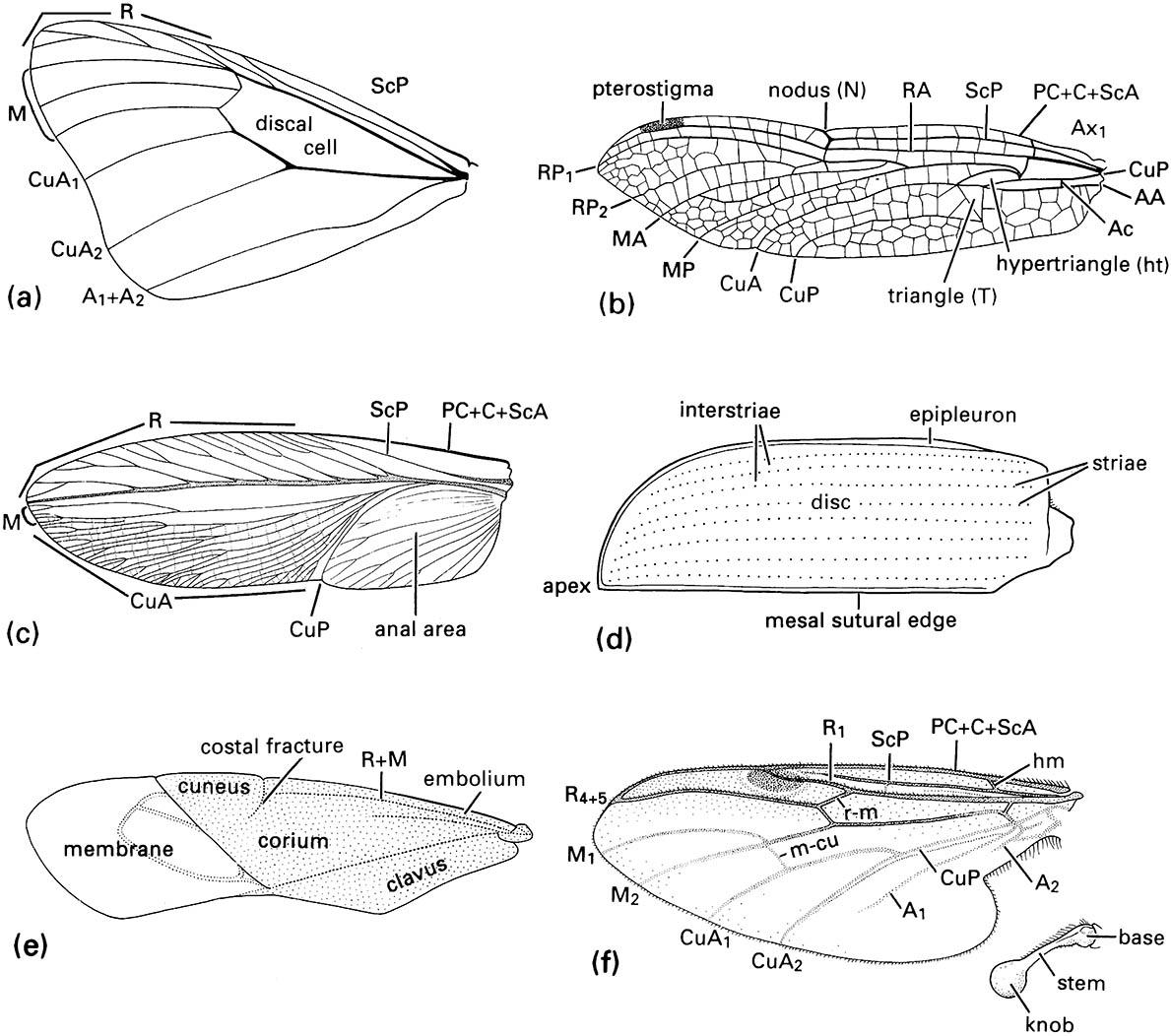

The Lepidoptera is one of the major insect orders, both in terms of size, with some 160,000 described species in more than 120 families, and in terms of popularity, with many amateur and professional entomologists studying the order, particularly the butterflies. Three of the four suborders contain few species and lack the characteristic proboscis of the largest suborder, Glossata, which contains the speciose series Ditrysia, defined by unique abdominal features especially in the genitalia. Adult lepidopterans range in size from very small (some microlepidopterans) to large (see Plates 1.1 & 1.3, facing here), with wingspans up to 30 cm. Development is holometabolous (vignette to Chapter 6). The head is hypognathous, bearing a long coiled proboscis (Fig. 2.12) formed from greatly elon- gated maxillary galeae; large labial palps are usually present, whereas other mouthparts are absent, although mandibles are primitively present. The compound eyes are large, and ocelli and/or chaetosemata (paired sensory organs lying dorsolateral on the head) are frequent. The antennae are multisegmented, often pectinate in moths (Fig. 4.6) and knobbed or clubbed in butterflies. The prothorax is small, with paired dorsolaterally placed plates (patagia), whereas the mesothorax is large and bears a scutum and scutellum, and a lateral tegula protects the base of each fore wing. The metathorax is small. The wings are completely covered with a double layer of scales (flattened modified macrotrichia), and hind and fore wings are linked by a frenulum, jugum, or simple overlap. Wing venation consists predominantly of longitudinal veins with few cross-veins and some large cells, notably the discal (Fig. 2.22a). The legs are long and usually gressorial, with five tarsomeres. The abdomen is 10-segmented, with segment 1 variably reduced, and segments 9 and 10 modifed as external genitalia (Fig. 2.23a). Internal female genitalia are very complex.

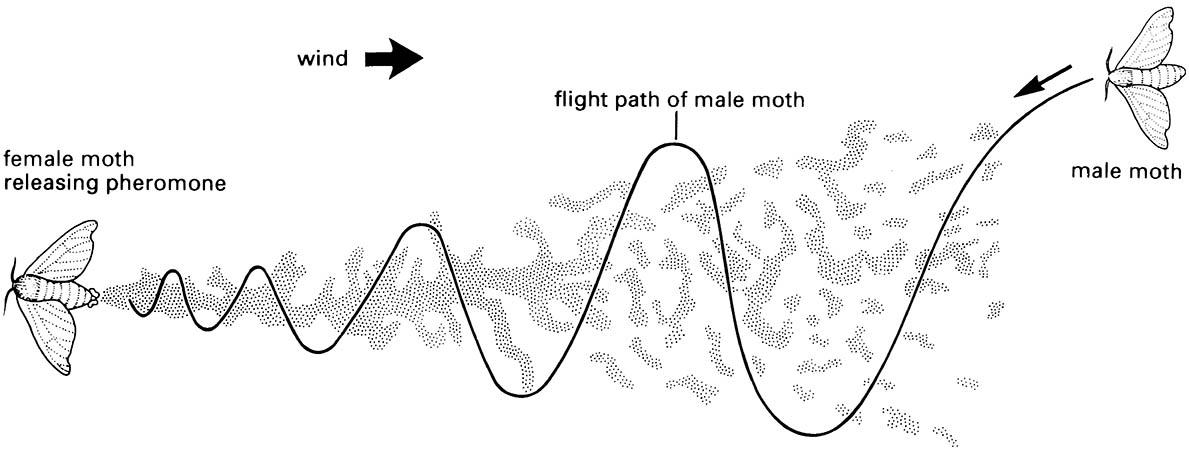

Premating behavior including courtship often involves pheromones (Figs. 4.7 & 4.8). Encounter between the sexes is often aerial, but copulation is on the ground or a perch. Eggs are laid on, close to or, more rarely, within a larval host plant. Egg numbers and degree of aggregation are very variable. Diapause is common.

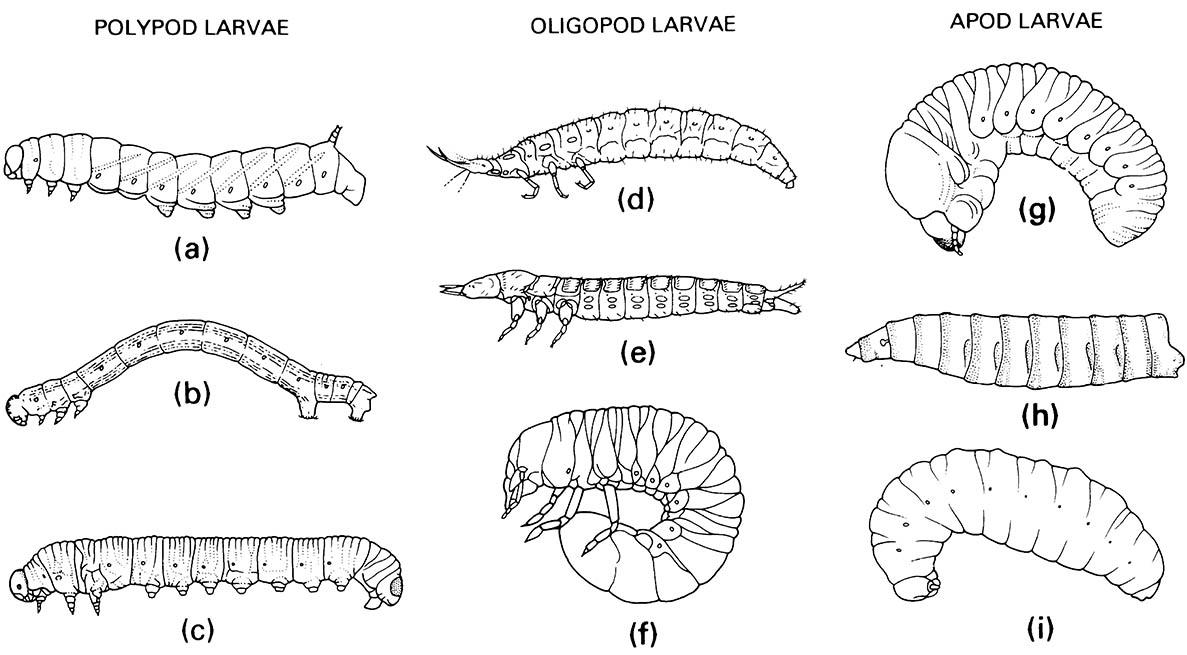

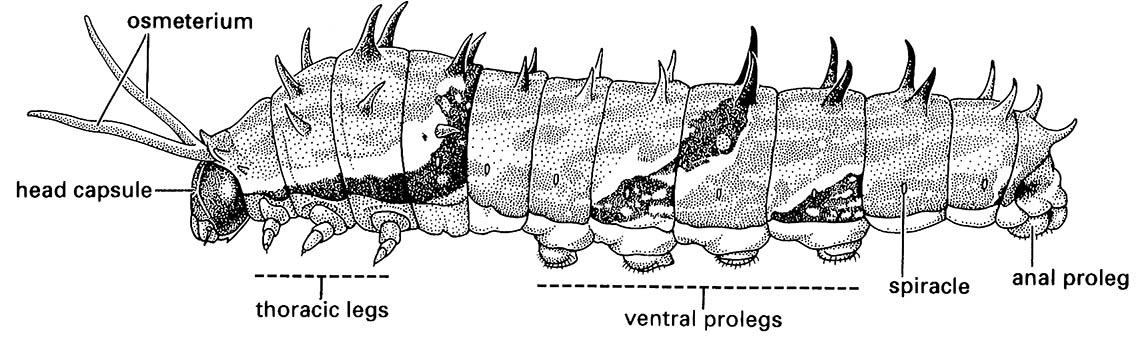

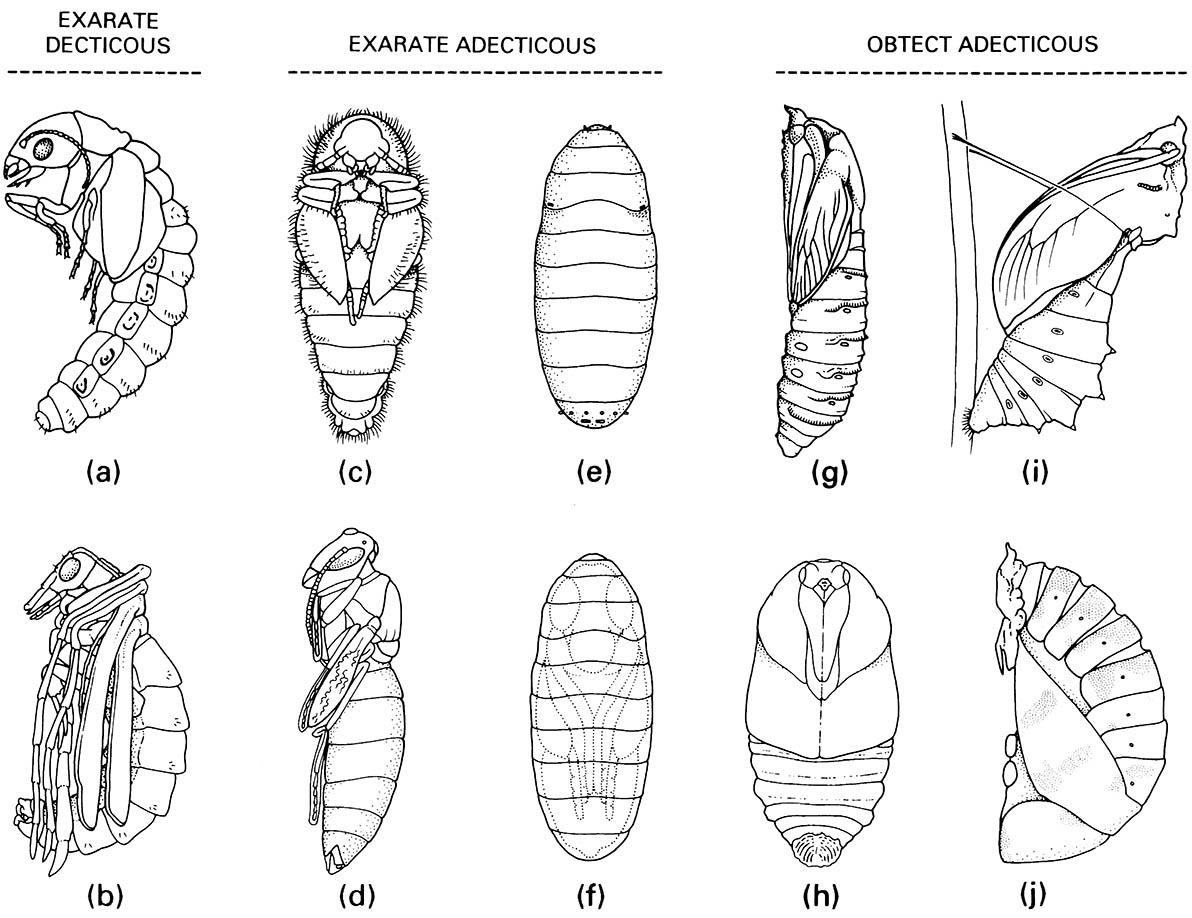

Lepidopteran larvae can be recognized by their sclerotized, hypognathous or prognathous head capsule, mandibulate mouthparts, usually six lateral stemmata (Fig. 4.9a), short three-segmented antennae, five- segmented thoracic legs with single claws, and 10-segmented abdomen with short prolegs on some seg- ments (usually on 3–6 and 10, but may be reduced) (Figs. 6.6a,b & 14.6). Silk-gland products are extruded from a characteristic spinneret at the median apex of the labial prementum. The pupa is usually contained within a silken cocoon, typically adecticous and obtect (a chrysalis) (Fig. 6.7g—i), with only some abdominal segments unfused; the pupa is exarate in primitive groups.

Adult lepidopterans that feed utilize nutritious liquids, such as nectar, honeydew, and other seepages from live and decaying plants, and a few species pierce fruit. However, none suck sap from the vessels of live plants. Many species supplement their diet by feeding on nitrogenous animal wastes. Most larvae feed exposed on higher plants and form the major insect phytophages; a few “primitive” species feed on non-angiosperm plants, and some feed on fungi. Several are predators and others are scavengers, notably amongst the Tineidae (wool moths).

The larvae are often cryptic (see Plate 5.2), particularly when feeding in exposed positions, or warningly colored (aposematic) to alert predators to their toxicity (Chapter 14). Toxins derived from larval food plants often are retained by adults, which show anti-predator devices including advertisement of non-palatability and defensive mimicry (section 14.5).

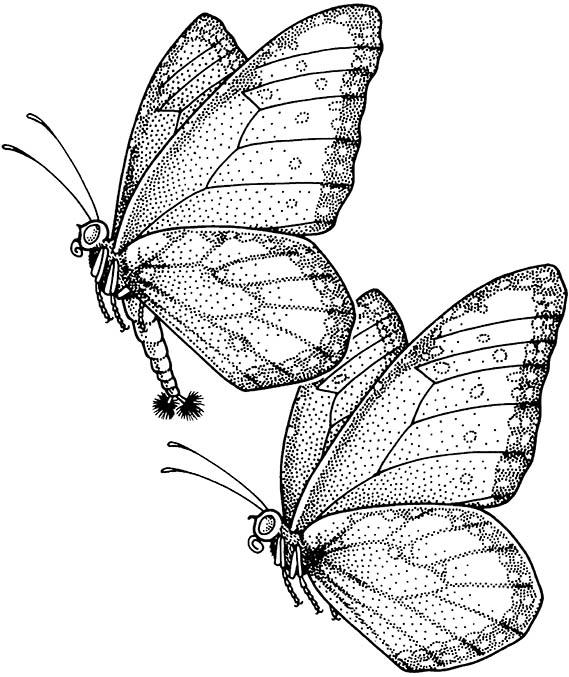

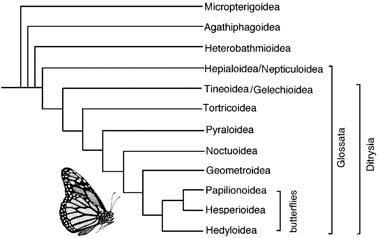

Although the butterflies popularly are considered to be distinct from the moths, they form a clade that lies deep within the phylogeny of the Lepidoptera: butterflies are not the sister group to all moths. Butterflies are day-flying whereas most moths are active at night or dusk. In life, butterflies hold their wings together vertically above the body (as shown here on the right for a cabbage white butterfly) in contrast to moths, which hold their wings flat or wrapped around the body (as shown on the left for the garden tiger moth); a few lepidopteran species have brachypterous adults and sometimes completely wingless adult females (see Plate 4.7).

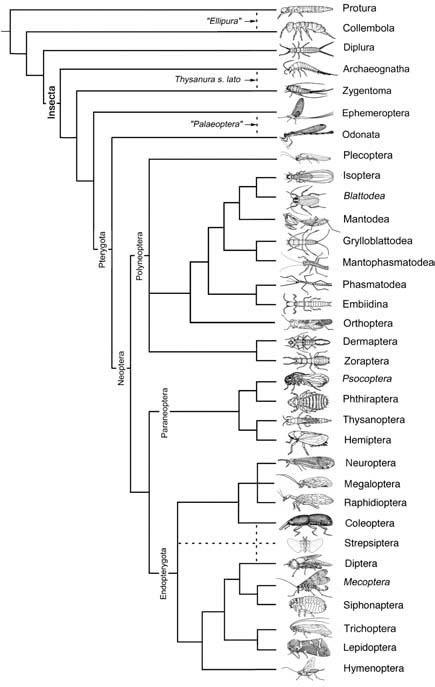

Phylogenetic relationships are considered in section 7.4.2 and depicted in Figs. 7.2 and 7.7.

(a) Positions of the proboscis showing, from left to right, at rest, with proximal region uncoiling, with distal region uncoiling, and fully extended with tip in two of many possible different positions due to flexing at «knee bend». (b) Lateral view of proboscis musculature. (c) Transverse section of the proboscis in the proximal region. (After Eastham & Eassa 1955)

(a) anterior view of head showing tripectinate antennae of this species; (b) cross-section through the antenna showing the three branches; (c) enlargement of tip of outer branch of one pectination showing olfactory sensilla.

(a) fore wing of a butterfly of Danaus (Lepidoptera: Nymphalidae); (b) fore wing of a dragonfly of Urothemis (Odonata: Anisoptera: Libellulidae); (c) fore wing or tegmen of a cockroach of Periplaneta (Blattodea: Blattidae); (d) fore wing or elytron of a beetle of Anomala (Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae); (e) fore wing or hemelytron of a mirid bug (Hemiptera: Heteroptera: Miridae) showing three wing areas — the membrane, corium, and clavus; (f ) fore wing and haltere of a fly of Bibio (Diptera: Bibionidae) (after J.W.H. Trueman, unpublished. ((a-d) After Youdeowei 1977; (f) after McAlpine 1981)

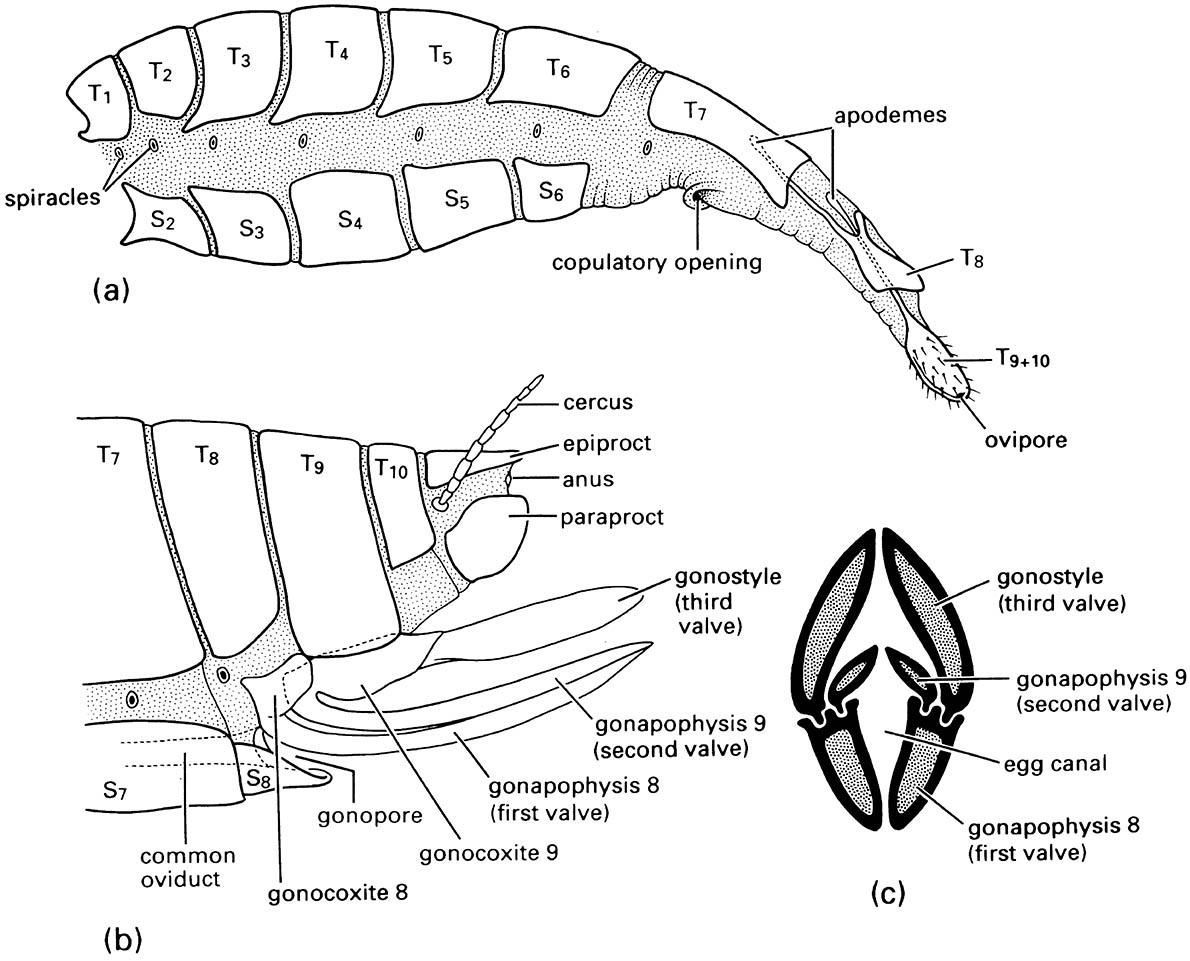

(a) lateral view of the abdomen of an adult tussock moth (Lepidoptera: Lymantriidae) showing the substitutional ovipositor formed from the extensible terminal segments; (b) lateral view of a generalized orthopteroid ovipositor composed of appendages of segments 8 and 9; (c) transverse section through the ovipositor of a katydid (Orthoptera: Tettigoniidae). T1—T10, terga of first to tenth segments; S2—S8, sterna of second to eighth segments. ((a) After Eidmann 1929; (b) after Snodgrass 1935; (c) after Richards & Davies 1959)

The pheromone trail forms a somewhat discontinuous plume because of turbulence, intermittent release, and other factors. (After Haynes & Birch 1985)

The male (above) has splayed hairpencils (at his abdominal apex) and is applying pheromone to the female (below). (After Brower et al. 1965)

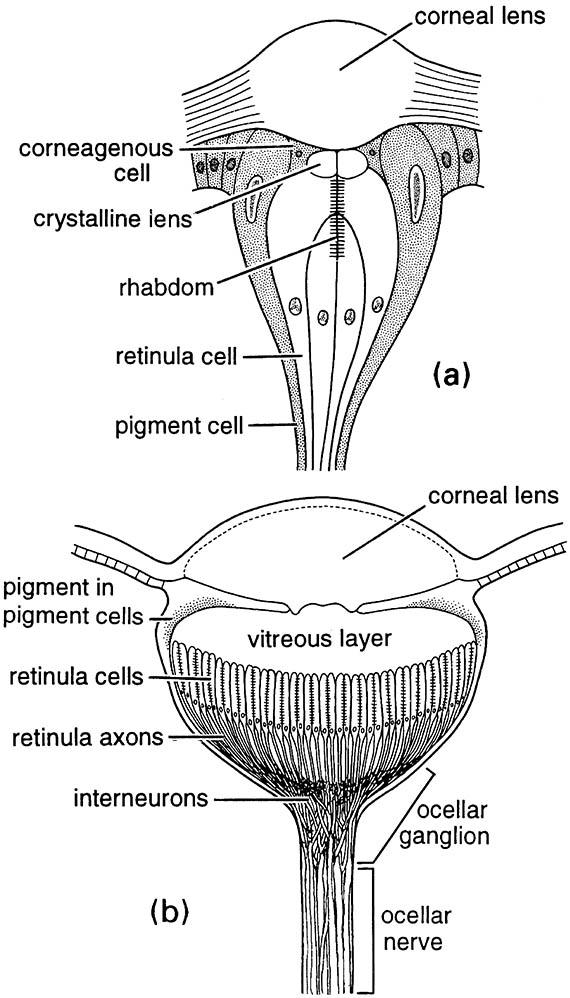

(a) a simple stemma of a lepidopteran larva; (b) a light-adapted median ocellus of a locust. ((a) After Snodgrass 1935; (b) after Wilson 1978)

(a) Lepidoptera: Sphingidae; (b) Lepidoptera: Geometridae; (c) Hymenoptera: Diprionidae. Oligopod larvae: (d) Neuroptera: Osmylidae; (e) Coleoptera: Carabidae; (f ) Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae. Apod larvae: (g) Coleoptera: Scolytidae; (h) Diptera: Calliphoridae; (i) Hymenoptera: Vespidae. ((a, e-g) After Chu 1949; (b, c) after Borror et al. 1989; (h) after Ferrar 1987; (i) after CSIRO 1970)

Eversion of this glistening, bifid organ occurs when the larva is disturbed and is accompanied by a pungent smell.

Exarate decticous pupae: (a) Megaloptera: Sialidae; (b) Mecoptera: Bittacidae. Exarate adecticous pupae: (c) Coleoptera: Dermestidae; (d) Hymenoptera: Vespidae; (e,f ) Diptera: Calliphoridae, puparium and pupa within. Obtect adecticous pupae: (g) Lepidoptera: Cossidae; (h) Lepidoptera: Saturniidae; (i) Lepidoptera: Papilionidae, chrysa lis; (j) Coleoptera: Coccinellidae. ((a) After Evans 1978; (b, c, e, g) after CSIRO 1970; (d) after Chu 1949; (h) after Common 1990; (i) after Common & Waterhouse 1972; (j) after Palmer 1914)

Broken lines indicate uncertain relationships. Thysanura sensu lato refers to Thysanura in the broad sense. (Data from several sources)

(After Kristensen & Skalski 1999)