Box 5.5. Egg-tending fathers — the giant water bugs

Care of eggs by adult insects is common in those that show sociality (Chapter 12), but tending solely by male insects is very unusual. This behavior is known best in the giant water bugs, the Nepoidea, comprising the families Belostomatidae and Nepidae whose common names — giant water bugs, water scorpions, toe biters — reflect their size and behaviors. These are predators, amongst which the largest species specialize in vertebrate prey such as tadpoles and small fish, which they capture with raptorial forelegs and piercing mouthparts. Evolutionary attainment of the large adult body size necessary for feeding on these large items is inhibited by the fixed number of five nymphal instars in Heteroptera and the limited size increase at each molt (Dyar’s rule; section 6.9.1). These phylogenetic (evolutionarily inherited) constraints have been overcome in intriguing ways — by the commencement of development at a large size via oviposition of large eggs, and in one family, with specialized paternal protection of the eggs.

Egg tending in the subfamily Belostomatinae involves the males “back-brooding” — carrying the eggs on their backs, in a behavior shared by over a hundred species in five genera. The male mates repeatedly with a female, perhaps up to a hundred times, thus guaranteeing that the eggs she deposits on his back are his alone, which encourages his subsequent tending behavior. Active male-tending behavior, called “brood-pumping”, involves underwater undulating “press-ups” by the anchored male, creating water currents across the eggs. This is an identical, but slowed-down, form of the pumping display used in courtship. Males of other taxa “surface-brood”, with the back (and thus eggs) held horizontally at the water surface such that the interstices of the eggs are wet and the apices aerial. This position, which is unique to brooding males, exposes the males to higher levels of predation. A third behavior, “brood-stroking”, involves the submerged male sweeping and circulating water over the egg pad. Tending results in > 95% successful emergence, in contrast to death of all eggs if removed from the male, whether aerial or submerged.

Members of the Lethocerinae, sister group to the Belostomatinae, show related behaviors that help us to understand the origins of aspects of these paternal egg defenses. Following courtship that involves display pumping as in Belostomatinae, the pair copulate frequently between bouts of laying in which eggs are placed on a stem or other projection above the surface of a pond or lake. After completion of egg-laying, the female leaves the male to attend the eggs and she swims away and plays no further role. The “emergent brooding” male tends the aerial eggs for the few days to a week until they hatch. His roles include periodically submerging himself to absorb and drink water that he regurgitates over the eggs, shielding the eggs, and display posturing against airborne threats. Unattended eggs die from desiccation; those immersed by rising water are abandoned and drown.

Insect eggs have a well-developed chorion that enables gas exchange between the external environment and the developing embryo (see section 5.8). The problem with a large egg relative to a smaller one is that the surface area increase of the sphere is much less than the increase in volume. Because oxygen is scarce in water and diffuses much more slowly than in air (section 10.3.1) the increased sized egg hits a limit of the ability for oxygen diffusion from water to egg. For such an egg in a terrestrial environment gas exchange is easy, but desiccation through loss of water becomes an issue. Although terrestrial insects use waxes around the chorion to avoid desiccation, the long aquatic history of the Nepoidea means that any such a mechanism has been lost and is unavailable, providing another example of phylogenetic inertia.

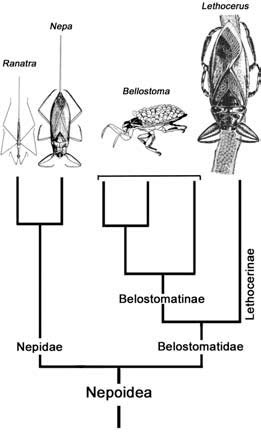

In the phylogeny of Nepoidea (shown opposite in reduced form from Smith 1997) a stepwise pattern of acquisition of paternal care can be seen. In the sister family to Belostomatidae, the Nepidae (the water-scorpions), all eggs, including the largest, develop immersed. Gas exchange is facilitated by expansion of the chorion surface area into either a crown or two long horns: the eggs never are brooded. No such chorionic elaboration evolved in Belostomatidae: the requirement by large eggs for oxygen with the need to avoid drowning or desiccation could have been fulfilled by oviposition on a wave-swept rock — although this strategy is unknown in any extant taxa. Two alternatives developed — avoidance of submersion and drowning by egg-laying on emergent structures (Lethocerinae), or, perhaps in the absence of any other suitable substrate, egg-laying onto the back of the attendant mate (Belostomatinae). In Lethocerinae, watering behaviors of the males counter the desiccation problems encountered during emergent brooding of aerial eggs; in Belostomatinae, the pre-existing male courtship pumping behavior is a pre-adaptation for the oxygenating movements of the back-brooding male. Surface-brooding and brood-stroking are seen as more derived male-tending behaviors.

The traits of large eggs and male brooding behavior appeared together, and the traits of large eggs and egg respiratory horns also appeared together, because the first was impossible without the second. Thus, large body size in Nepoidea must have evolved twice. Paternal care and egg respiratory horns are different adaptations that facilitate gas exchange and thus survival of large eggs.