Box 13.4. Neuropterida, or neuropteroid orders

Members of these three small neuropteroid orders have holometabolous development, and are mostly predators. Approximate numbers of described species are: 5000–6000 for Neuroptera (lacewings, owlflies, antlions) in about 20 families; 300 in Megaloptera (alderflies and dobsonflies) in two widely recognized families; and 200 in Raphidioptera (snakeflies) in two families.

Adults have multisegmented antennae, large separated eyes, and mandibulate mouthparts. The prothorax may be larger than the meso- and metathorax, which are about equal in size. The legs may be modified for predation. Fore and hind wings are similar in shape and venation, with folded wings often extending beyond the abdomen. The abdomen lacks cerci.

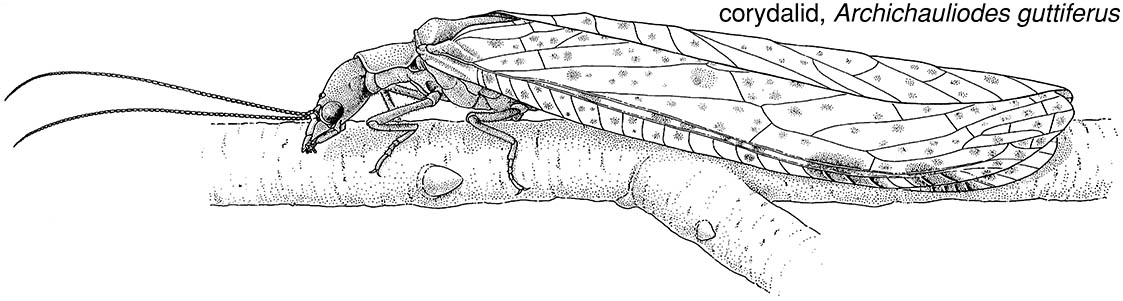

Megaloptera (see Appendix) are predatory only in the aquatic larval stage (Box 10.6) — although the adults have strong mandibles, these are not used in feeding. Adults (such as the corydalid, Archichauliodes guttiferus, illustrated here) closely resemble neuropterans, except for the presence of an anal fold in the hind wing. The pupa (Fig. 6.7a) is mobile.

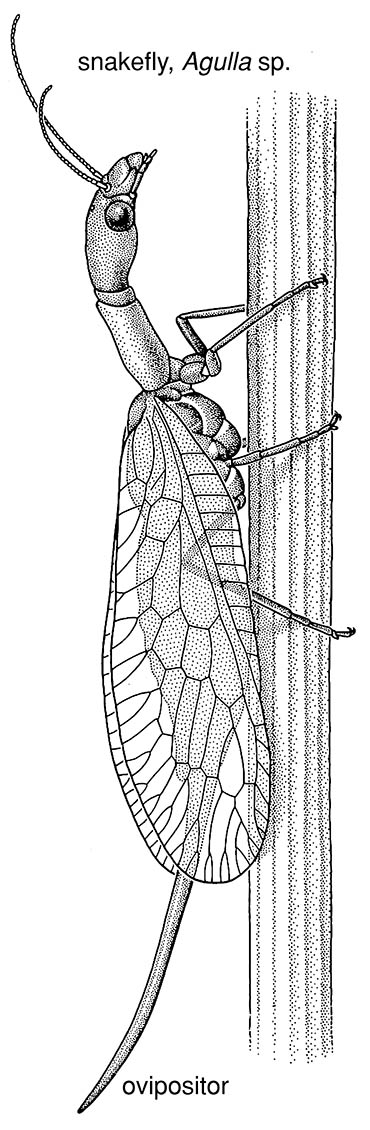

Raphidioptera are terrestrial predators both as adults and larvae. The adult is mantid-like, with an elongate prothorax — as shown here by the female snakefly of an Agulla sp. (Raphidiidae) (after a photograph by D.C.F. Rentz) — and mobile head used to strike, snake like, at prey. The larva (illustrated in the Appendix) has a large prognathous head, and a sclerotized prothorax that is slightly longer than the membranous meso- and metathorax. The pupa is mobile.

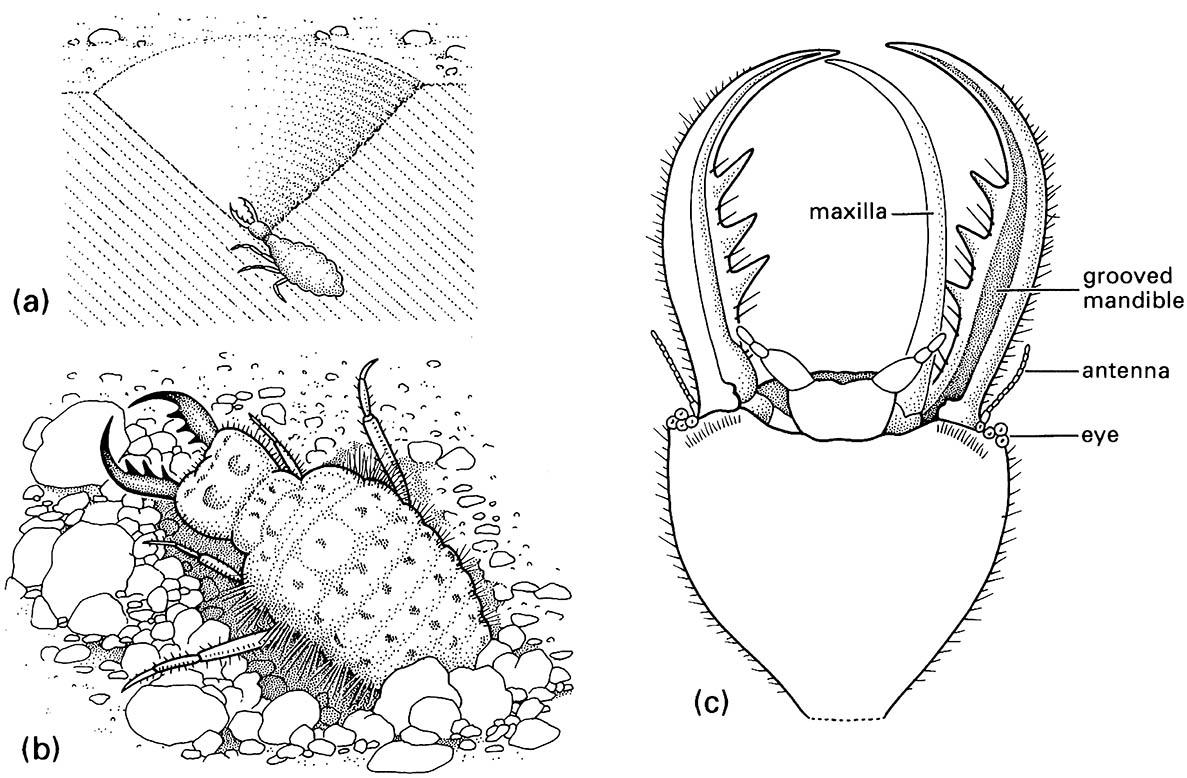

Adult Neuroptera (illustrated in Fig. 6.12 and the Appendix, and exemplied here by an owlfly, Ascalaphus sp. (Ascalaphidae), after a photograph by C.A.M. Reid) possess wings typically with numerous cross-veins and “twigging” at ends of veins; many are predators, but nectar, honeydew, and pollen are consumed by some species. Neuropteran larvae (Fig. 6.6d) are usually specialized, active predators, with prognathous heads and slender, elongate mandibles and maxillae combined to form piercing and sucking mouthparts (Fig. 13.2c); all have a blind-ending hind gut. Larval dietary specializations include spider egg masses (for Mantispidae), freshwater sponges (for Sisyridae; Box 10.6), or soft- bodied hemipterans such as aphids and scale insects (for Chrysopidae, Hemerobiidae, and Coniopterygidae). Pupation is terrestrial, within shelters spun with silk from Malpighian tubules. The pupal mandibles are used to open a toughened cocoon.

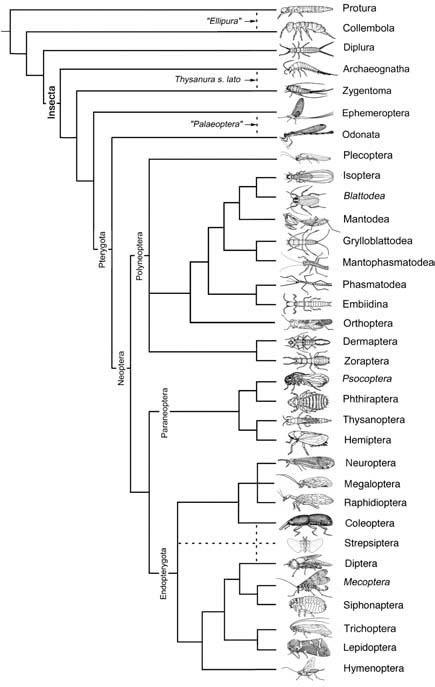

The Megaloptera, Raphidioptera, and Neuroptera are treated here as separate orders; however, some authorities include the Raphidioptera in the Megaloptera, or all three may be united in the Neuroptera. Phylogenetic relationships are considered in section 7.4.2 and depicted in Fig. 7.2.

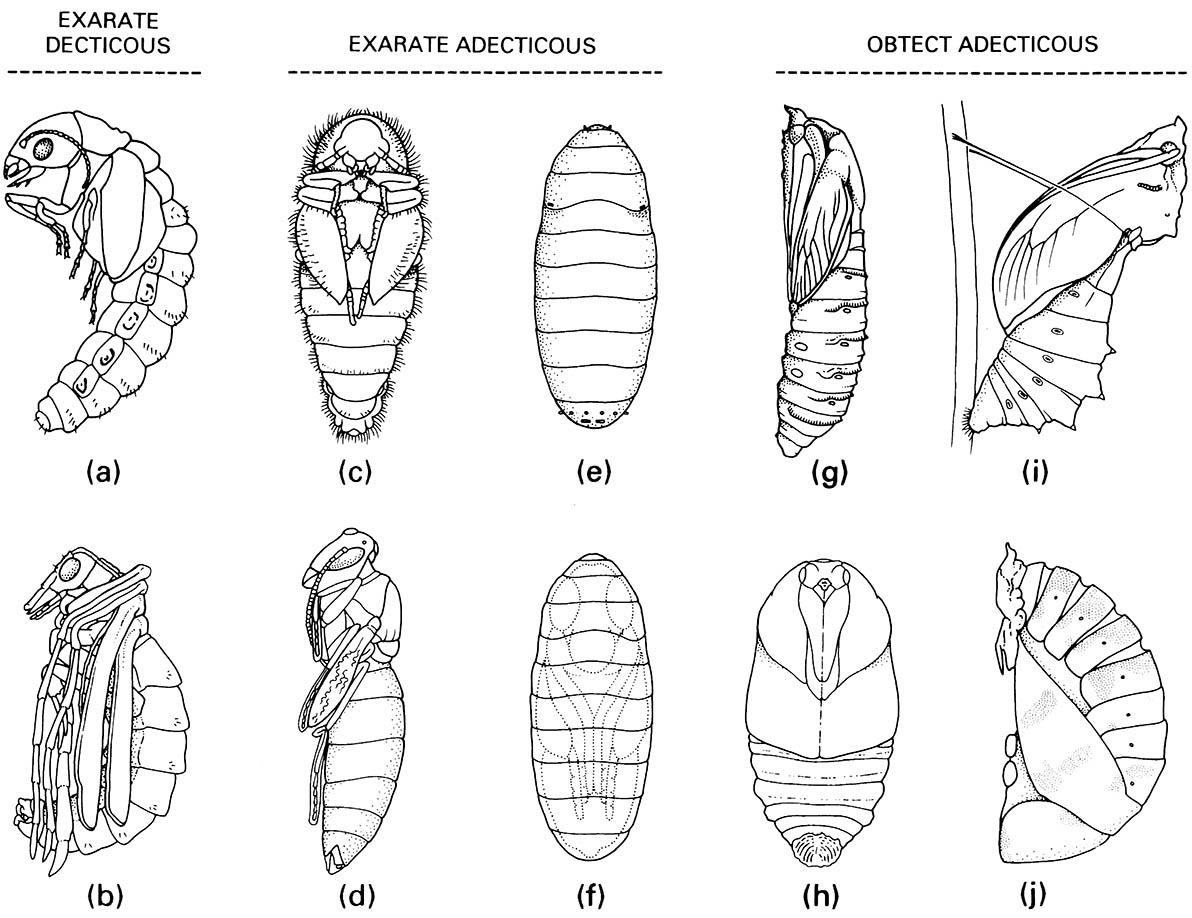

Exarate decticous pupae: (a) Megaloptera: Sialidae; (b) Mecoptera: Bittacidae. Exarate adecticous pupae: (c) Coleoptera: Dermestidae; (d) Hymenoptera: Vespidae; (e,f ) Diptera: Calliphoridae, puparium and pupa within. Obtect adecticous pupae: (g) Lepidoptera: Cossidae; (h) Lepidoptera: Saturniidae; (i) Lepidoptera: Papilionidae, chrysa lis; (j) Coleoptera: Coccinellidae. ((a) After Evans 1978; (b, c, e, g) after CSIRO 1970; (d) after Chu 1949; (h) after Common 1990; (i) after Common & Waterhouse 1972; (j) after Palmer 1914)

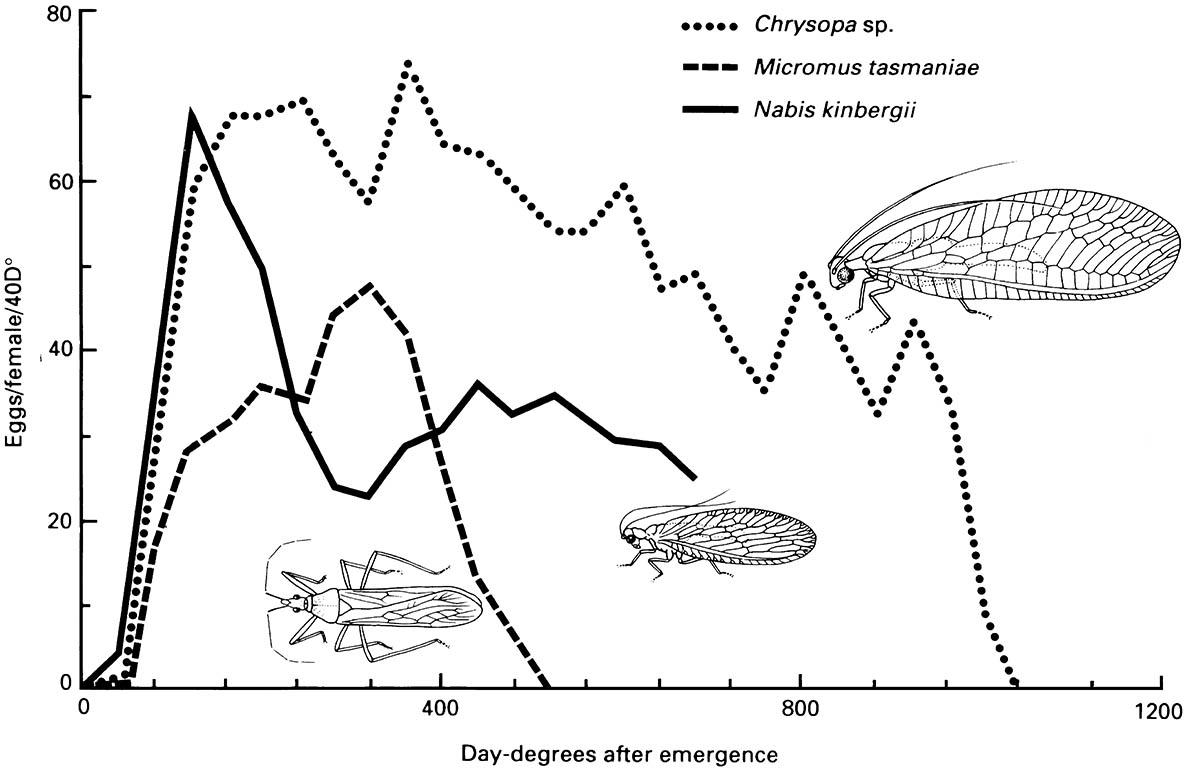

(After Samson & Blood 1979)

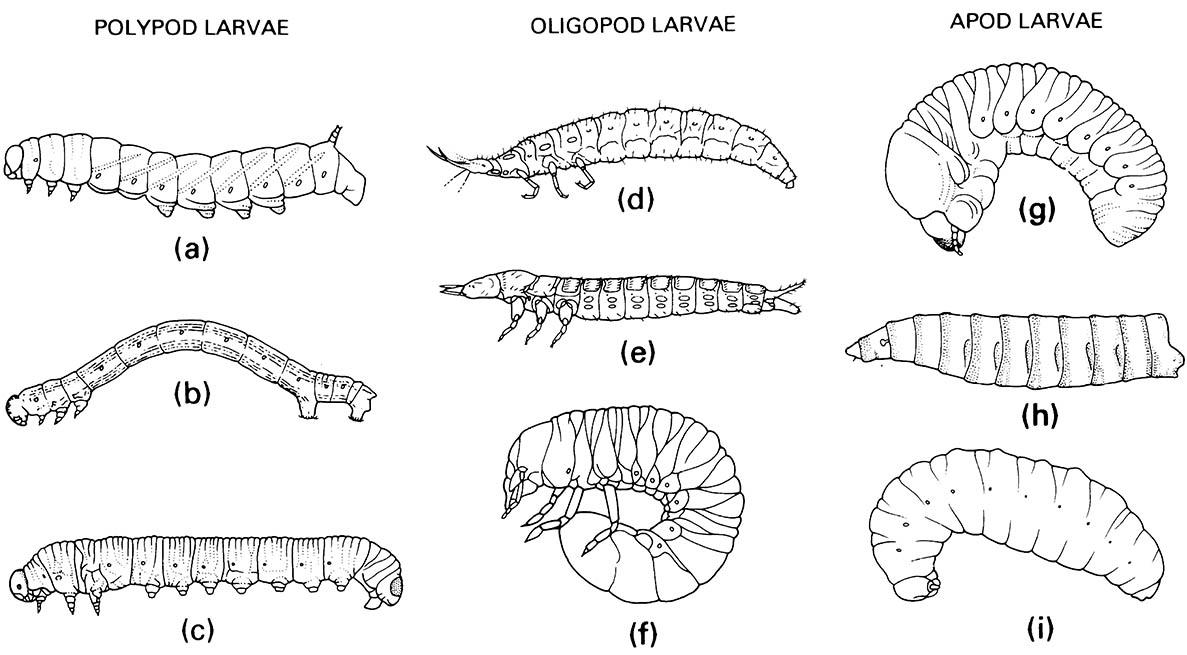

(a) Lepidoptera: Sphingidae; (b) Lepidoptera: Geometridae; (c) Hymenoptera: Diprionidae. Oligopod larvae: (d) Neuroptera: Osmylidae; (e) Coleoptera: Carabidae; (f ) Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae. Apod larvae: (g) Coleoptera: Scolytidae; (h) Diptera: Calliphoridae; (i) Hymenoptera: Vespidae. ((a, e-g) After Chu 1949; (b, c) after Borror et al. 1989; (h) after Ferrar 1987; (i) after CSIRO 1970)

(a) larva in its pit in sand; (b) detail of dorsum of larva; (c) detail of ventral view of larval head showing how the maxilla fits against the grooved mandible to form a sucking tube. (After Wigglesworth 1964)

Broken lines indicate uncertain relationships. Thysanura sensu lato refers to Thysanura in the broad sense. (Data from several sources)