Box 5.3. Sperm precedence

The penis or aedeagus of a male insect may be modified to facilitate placement of his own sperm in a strategic position within the spermatheca of the female or even to remove a rival’s sperm. Sperm displacement of the former type, called stratification, involves pushing previously deposited sperm to the back of a spermatheca in systems in which a “last-in-first-out” principle operates (i.e. the most recently deposited sperm are the first to be used when the eggs are fertilized). Last-male sperm precedence occurs in many insect species; in others there is either first-male precedence or no precedence (because of sperm mixing). In some dragonflies, males appear to use inflatable lobes on the penis to reposition rival sperm. Such sperm packing enables the copulating male to place his sperm closest to the oviduct. However, stratification of sperm from separate inseminations may occur in the absence of any deliberate repositioning, by virtue of the tubular design of the storage organs.

A second strategy of sperm displacement is removal, which can be achieved either by direct scooping out of existing sperm prior to depositing an ejaculate or, indirectly, by flushing out a previous ejaculate with a subsequent one. An unusually long penis that could reach well into the spermathecal duct may facilitate flushing of a rival’s sperm from the spermatheca. A number of structural and behavioral attributes of male insects can be interpreted as devices to facilitate this form of sperm precedence, but some of the best known examples come from odonates.

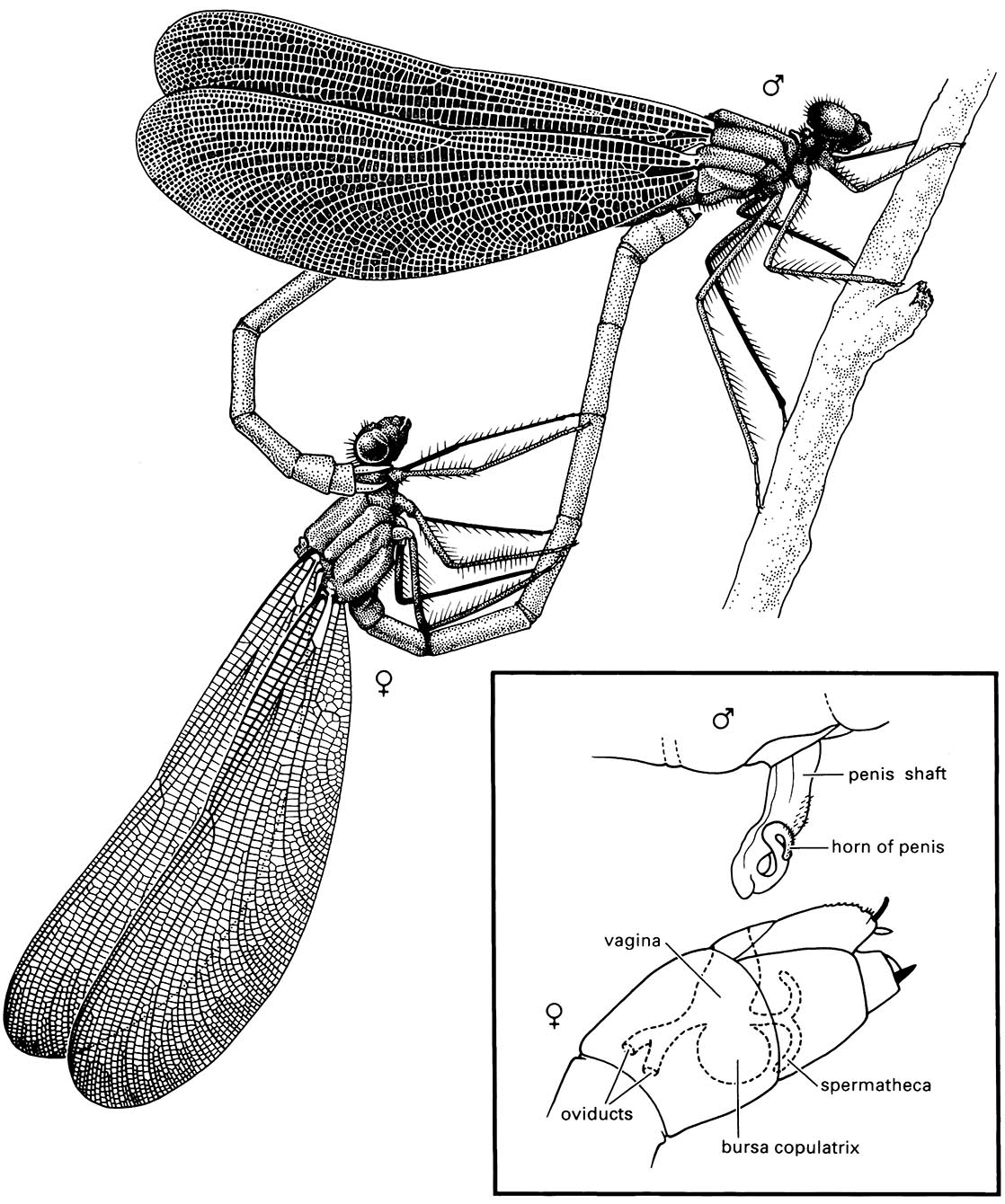

Copulation in Odonata involves the female placing the tip of her abdomen against the underside of the anterior abdomen of the male, where his sperm are stored in a reservoir of his secondary genitalia. In some dragonflies and most damselflies, such as the pair of copulating Calopteryx damselflies (Calopterygidae) illustrated opposite in the wheel position (after Zanetti 1975), the male spends the greater proportion of the copulation time physically removing the sperm of other males from the female’s sperm storage organs (spermathecae and bursa copulatrix). Only at the last minute does he introduce his own. In these species, the male’s penis is structurally complex, sometimes with an extensible head used as a scraper and a flange to trap the sperm plus lateral horns or hook-like distal appendages with recurved spines to remove rival sperm (inset to figure; after Waage 1986). A male’s ejaculate may be lost if another male mates with the female before she oviposits. Thus, it is not surprising that male odonates guard their mates, which explains why they are so frequently seen as pairs flying in tandem.