American Grasshopper, Schistocerca americana (Drury)

This grasshopper is found widely in eastern North America, from southern Canada (where it is an occasional invader) south through Mexico to northern South America. In the midwestern states, where it is common, the resident population receives a regular infusion of dispersants from southern locations. In the southeast it is quite common, and one of the few species to reach epidemic densities. It is native to North America.

Life History

In warm climates, American grasshopper has two generations per year and overwinters in the adult stage. In Florida, eggs produced by overwintered adults begin to hatch in April-May, producing spring generation adults by May-June. This spring generation produces eggs that hatch in AugustSeptember. The adults from this autumn generation survive the winter.

The eggs of S. americana initially are light orange in color, turning tan with maturity. They are elongate-spherical in shape, widest near the middle, and measure about 7.5 mm in length and

2.0 mm in width. The eggs are clustered together in a whorled arrangement, and number

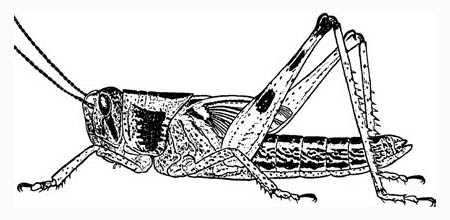

Normally there are six instars in this grasshopper though sometimes only five. The young grasshoppers are light green in color. They are extremely gregarious during the early instars. At low densities the nymphs remain green throughout their development, but normally gain increasing amounts of black, yellow, and orange coloration commencing with the third instar. Instars can be distinguished by their antennal, pronotal, and wing development. The first and second instars display little wing development but have 13 and

17 antennal segments, respectively. In the third instar, the number of antennal segments increases to

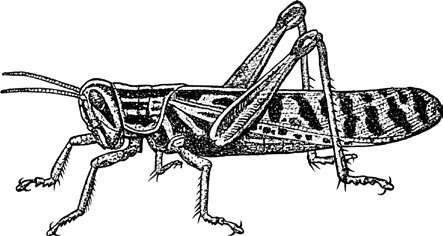

The adult (Fig. 40) is rather large, but slender bodied, measuring

Adults are active, flying freely and sometimes in swarms. They normally are found in sunny areas, but during the warmest portions of the day will move to shade. Adults are long lived, persisting for months in the laboratory and apparently in the field as well. This can lead to early-season situations where overwintered adults, all instars of nymphs, and new adults are present simultaneously. Mild winters favor survival of overwintering adults and apparently lead to population increase if summer weather and food supplies also are favorable.

Adults of American grasshopper tend to be arboreal in habit, and a great deal of the feeding by adults occurs on forest, shade, and fruit trees. The nymphs, however, feed on a large number of grasses and broadleaf plants, both wild and cultivated. During periods of abundance, almost no plants are immune to attack, and vegetables, grain crops, and ornamental plants are injured. American grasshopper consumes bean, corn, okra, and yellow squash over some other vegetables when provided with choices, but free-flying adults normally avoid low-growing crops such as vegetables, corn (maize) being a notable exception.

The natural enemies of S. americana are not well known. Birds such as mockingbirds, Mimus polyglottos polyglottos (Linnaeus), and crows, Corvus brachyrhynchos brachyrhynchos Brehm have been observed to feed on these grasshoppers. Fly larvae, Sarcophaga sp. (Diptera: Sarcophagidae) are sometimes parasitic on overwintering adults. Fungi have also been investigated for grasshopper suppression and Metarhizium anisopliae var. acridum kills American grasshopper quickly under laboratory conditions. This fungus is effective under adverse field conditions in Africa, so it may prove to be a useful suppression tool.

Damage

Grasshoppers are defoliators, eating irregular holes in leaf tissue. Under high density conditions they can strip vegetation of leaves, but more commonly leave plants with a ragged appearance. American grasshopper displays a tendency to swarm, and the high densities of grasshoppers can cause severe defoliation.

Because American grasshopper is a strong flier, it also sometimes becomes a contaminant of crops. When the late-season crop of collards in the Southeast is harvested mechanically, for example, American grasshopper may become incorporated into the processed vegetables. Although most grasshoppers can be kept from dispersing into crops near harvest by treating the periphery of the crop field, it is much more difficult to prevent invasion by American grasshopper because it may fly over any such barrier treatments.

Populations normally originate in weedy areas such as fence rows and abandoned fields. Thus, margins of fields are first affected and this is where monitoring should be concentrated. It is highly advisable to survey weedy areas in addition to crop margins if grasshoppers are found, as this gives an estimate of the potential impact if the grasshoppers disperse into the crop. Also, it is important to recognize that this species is highly dispersive in the adult stage, and will fly hundreds of meters or more to feed.

Management

Foliar applications of insecticides will suppress grasshoppers, but they are difficult to kill, particularly as they mature. Bait formulations are not usually recommended because these grasshoppers spend little time on the soil surface, preferring to climb high in vegetation.

Land management is an important element of S. americana population regulation. Grasshopper densities tend to increase in large patches of weedy vegetation that follow the cessation of agriculture or the initiation of pine tree plantations. In both cases, the mixture of annual and perennial forbs and grasses growing in fields that are untilled seems to favor grasshopper survival, with the grasshoppers then dispersing to adjacent fields as the most suitable plants are depleted. However, as abandoned fields convert to dense woods or the canopy of pine plantations shades the ground and suppresses weeds, the suitability of the habitat declines for grasshoppers.

Disturbance or maturation of crops may cause American grasshopper to disperse, sometimes over long distances, into crop fields. Therefore, care should be taken not to cut vegetation or till the soil of fields harboring grasshoppers if a susceptible crop is nearby. Planting crops in large blocks reduces the relative amount of crop edge, and the probability that a crop plant within the field will be attacked.

Figure 40 Adult of American grasshopper, Schistocerca americana (Drury).

Figure 41 Sixth instar of American grasshopper, Schistocerca americana (Drury).

American False Tiger Moths