Alfalfa Leafcutting Bee, Megachile rotundata

The alfalfa leafcutting bee, Megachile rotundata Fabricius (Hymenoptera: Megachilidae), has been successfully semi-domesticated within the last 50 years to pollinate alfalfa for seed production in North America. Honey bees are inefficient pollinators of alfalfa and, although bumbles bees and some other wild bees are efficient pollinators, they have proved difficult to manage. The use of the alfalfa leafcutting bee has succeeded in greatly increasing the seed yield of alfalfa. In western Canada, the average alfalfa seed yield using this bee exceeds 300 kg/ha, whereas without it is usually less than 50 kg/ha. The genus Megachile contains many species that nest in tunnels in dead trees or fallen logs. Most are solitary, but M. rotundata is gregarious and, although each female constructs and provisions her own tunnel, she will tolerate close neighbors. This behavioral characteristic is one of the main reasons why this species has been amenable to management on a commercial scale. M. rotundata is of eastern Mediterranean origin and was first found in North America in the 1940s near seaports. It probably gained entry as diapausing pre-pupae within tunnels in the wood used to make shipping crates or pallets.

Life History

Once a suitable tunnel has been found, the female uses her mandibles to neatly cut oblong pieces of leaves or flower petals which she uses to build cells end to end in the tunnel, starting at the far end and finishing near the entrance (Fig. 32). About 15 leaf pieces are arranged in overlapping layers and cemented together to form a thimbleshaped cell with a concave bottom. The cell is then provisioned with nectar and pollen. During this process, the female enters the tunnel head first, regurgitates the nectar, then turns around to remove the pollen from the scopa (the pollencollecting hairs on the underside of her abdomen) and tamps the pollen into the nectar with the tip of her abdomen. The provisions for each cell consist of about two-thirds nectar and one-third pollen, requiring

Domestication

The gregarious nature of M. rotundata and its willingness to accept artificial domiciles has permitted the commercial scale management of this species for crop pollination. Initially, observant alfalfa seed producers in the northwestern U.S.A. noticed that this species, which had undergone a population increase following natural establishment, would nest in man-made structures such as shingled roofs and they started to provide artificial tunnels by drilling holes in logs positioned around the edges of the seed fields. The next step was to provide nests consisting of wooden blocks drilled with closely spaced tunnels. Although reasonably successful on a small scale, this method was not suitable for the management of the large numbers of bees (50,000—75,000/ha) required for commercial alfalfa seed production. Consequently a “loosecell” system was developed. This system uses 10 mm thick boards of wood or polystyrene which are grooved on both sides and stacked together to form hives of closely packed tunnels about 7 mm in diameter and 150 mm in length. At the end of the season, the boards are separated and the cells removed using specialized automated equipment. Aſter being stripped from the boards the cells are tumbled and screened to remove loose leaf pieces, molds and some parasites and predators. The clean cells are then placed in containers for overwintering storage at about 50% R.H. and 5°C. In the spring, the cells are placed in trays for incubation at 70%

R.H. and 30°C. A few days before the bees are due to emerge, the trays are moved to especially designed shelters spaced throughout the alfalfa seed fields. By selecting the date when incubation begins, and if necessary manipulating the incubation temperature, the emergence of the bees can be adjusted to coincide with the start of alfalfa bloom.

An advantage of the loose cell system of management is that it facilitates the control of parasitoids, predators and disease, and assessment of the quality of the progeny. Leafcutting beekeepers routinely send samples of cells to specialized leafcutting bee “cocoon” testing centers, where they are

Natural Enemies

About 20 species of insects are known to parasitize or prey on the immature stages of the alfalfa leafcutting bee. The most important of these are several species of chalcid wasps, including Pteromalus venustus Walker, Monodontomerus obscurus Westwood, Melittobia chalbii Ashmead and Diachys confusus (Girault). The most widespread and damaging is P. venustus, which probably arrived in North America with its host. The female parasitoid pierces the host cocoon with her ovipositor, stings the larva or pupa to paralyze it, and then lays some eggs on its surface. The parasitoid larvae then feed upon the bee larva eventually killing it. Normally

Two other enemies, which are more of biological interest than economic significance, are several species of cuckoo bees, Coelioxys (Megachilidae) and the brown blister beetle, Nemognatha lutea LeConte. Cuckoo bees are very similar to leafcutting bees, but lack the structures required for collecting pollen. The female cuckoo bee lays her egg in the partially provisioned cell of the leafcutting bee while the rightful owner is out foraging. When partly grown, the cuckoo bee larva kills the leafcutting bee larva and usurps the provisions. Brown blister beetle females lay their eggs on flowers and the first instar larvae (triungulins) attach themselves to any bee that visits the flower. When the bee returns to its nest, the triungulin detaches and begins feeding on the cell contents, destroying 2 or 3 cells before reaching maturity.

Several stored-product insects including the driedfruit moth, Vitula edmandsae serratilinnella Ragonot, and stored-product beetles such as the sawtoothed grain beetle, Oryzaephilus surinamensis (Linnaeus), the red flour beetle, Tribolium castaneum (Herbst) and the confused flour beetle, Tribolium confusum (Jacquelin du Val) can cause serious damage during overwintering storage, especially if sanitation practices are lax.

Most of the parasitoids and predators can be largely controlled by proper construction of hives and nesting materials, physical removal during the loose-cell processing and strict hygiene during storage. However, successful control of the major pest, the chalcid P. venustus, oſten requires carefully controlled fumigation using dichlorvos (2, 2-dichloro-vinyl dimethyl phosphate) resin strips.

The only disease causing significant losses to the leafcutting bee industry is chalkbrood, caused by the fungus Ascosphaera aggregata Skou. The disease was first reported in leafcutting bees in 1973, and remains most severe in the western U.S. states, where losses of more than 65% of bees are not uncommon. Bee larvae become infected aſter consuming pollen provisions contaminated with the fungal spores which germinate within the midgut and penetrate into the hemocoel. Larvae soon die and turn a chalk white color as the mycelium fills the body. Sporogenesis occurs beneath the host cuticle resulting in the formation of ascospores which are bound in “spore balls” within ascomata. At this stage, the cadaver turns black. Spores are spread by adults that must chew their way through infected cadavers in order to exit their nesting tunnels. Chalkbrood can be adequately managed through strict hygiene and decontamination of the bee cells, nest materials and shelters. Initially, decontamination was performed by dipping in household bleach. However, fumigation with paraformaldehyde has become the method of choice, and is highly effective for the control of both A. aggregata and foliar molds, which can sometimes pose a health risk to the beekeeper.

Alfalfa leafcutting bee, Megachile rotundata.

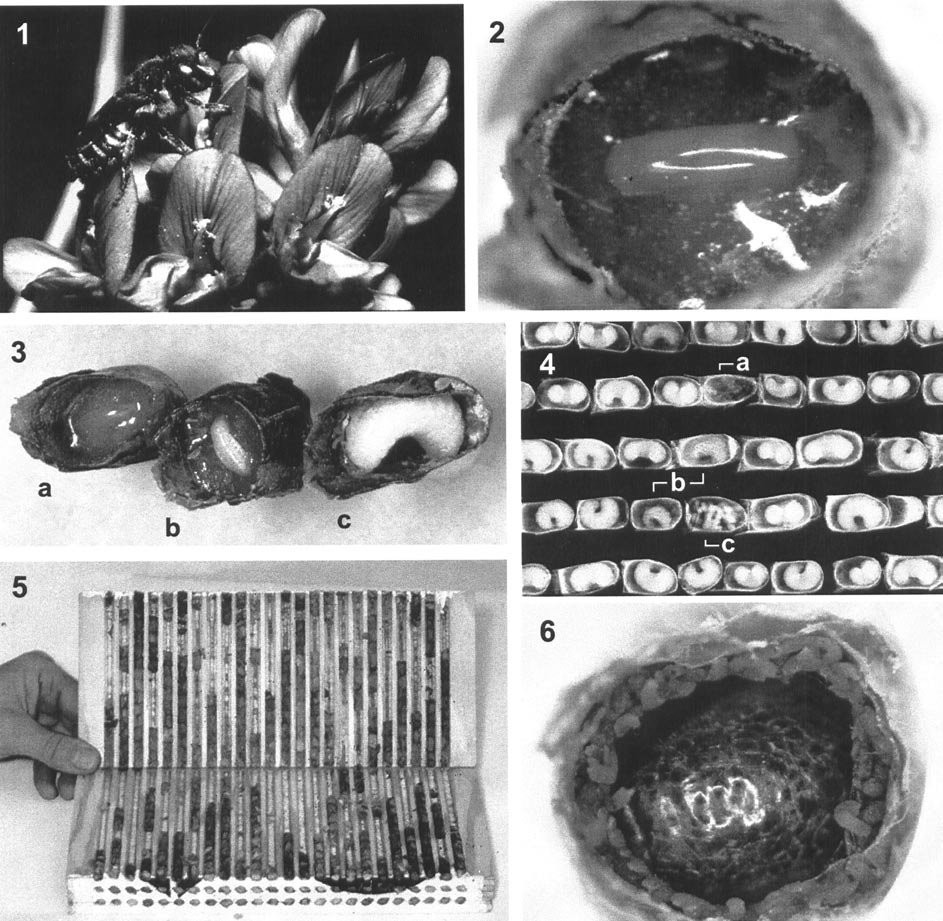

(1) Adult on alfalfa flower. Flowers are pollinated while the bees visit the flowers to collect nectar and pollen for provisioning their cells.

(2) A single egg is deposited on the surface of pollen/ nectar provisions within a cell which the female constructs within tunnels using oblong pieces of leaves or flower petals.

(3) The egg placed into the cell hatches within 2 to 3 days and the larva immediately begins to consume the provisions. The larva pupates after undergoing 4 instars. (a) single egg, (b) 3rd instar, and © 4th instar larvae within the cell. Cell caps have been removed.

(4)

(5) Nesting boards separated to show arrangement of bee cells constructed within the tunnels. In the fall, the boards are removed from the field and the cells are stripped from the boards using specialized automated equipment.

(6) Chalkbrood cadaver within the cell. Note the ring of frass deposited on the outside edge of the cell. Normally, the larva would spin a tough silken cocoon within which it overwinters as a diapausing pre-pupa. Larvae infected with chalkbrood usually succumb just after defecating and just prior to cocoon spinning.

Alexander, Charles Paul